Last month, Pau Waelder, who I had the pleasure meeting with during a panel discussion at CCB in 2012, interviewed Dave Griffiths, Marloes de Valk and myself for the Fundación Telefónica. The purpose of the discussion was to reflect back on Naked on Pluto, a work that won the foundation VIDA award back in 2011.

The interview is available in English and Castilian.

Below a copypasta of the English version, for local archiving.

You created Naked on Pluto, a project on privacy and social networks that won the First Prize at VIDA 13.2. What drove your attention towards social networks and Facebook in particular, and how did you develop the project?

Dave: I’m interested in a technology like this when it starts being used by people who are not interested in technology. At the start of the Naked on Pluto project, social networking was reaching vast audiences. For many people then –as now– Facebook was the Internet. For some it’s the first time they use a computer. This provides a fascinating space to explore possibilities, probe the reasons why things were made the way they were – look for and document hidden assumptions of the engineers and business practices that surround the networks. We started out by researching the Facebook api and writing small prototypes to see what we could do, how it felt to be given this power – to pull data from users (with ourselves as test cases) and look at it in different contexts, and try and get some of this feeling into the game design.

Marloes: What drove my attention towards social networks was the change they brought about in my own environment. As the use of platforms like Twitter and Facebook increased, they became the new preferred mode of communication, replacing text messaging and email for a large part. It changed social mechanics in a way. Not sharing and not using these platforms meant partial social exclusion. Sharing parts of your life via social media became a new status symbol, with amounts of friends, followers, likes, etc. as measures. This of course had a big impact on other parts of life, such as the amount of time spent using mobile devices. Only one year after we started work on Naked on Pluto the first social media addiction rehab clinic appeared. It’s been quite a revolution and a very interesting one. It raises questions about social behavior and the impact technology and economy have on it. A fantastic starting point for an artistic investigation.

Facebook is well known for sending cease and desist letters to other artistic projects that have automated tasks within their platform, such as Web 2.0 Suicide Machine or Seppukoo. Did you have problems with this company due to the use of bots that cull information from the player’s profile?

Aymeric: Not at all. We can only speculate on the reasons why. My personal theory as for why we managed to stay either under the radar or irrelevant to Facebook concerns goes like this: 1. We have not made any direct confrontation with Facebook that would lead to ridicule directly the company or influence its users to leave the platform. Of course Elastic Versailles is the embodiment of everything we think is wrong with Facebook and I personally hope that whoever has been exposed with the game, and the research we made around it, will at least have a better grasp about the ill-formed notion of online privacy. Yet this is not something literally expressed in the application itself. 2. We have made sure, in every possible details, that we are not breaking any terms of service or using deceptive techniques to engage more users in the application. 3. We have left the application in what Facebook calls a developer’s sandbox, which, while making it fully playable, prevents the application from being visible in Facebook game directory, making the work spreading through the word of mouth, more or less. All these decisions were consciously made, we wanted Naked on Pluto to be a humble constant background noise, and not a hyped peak.

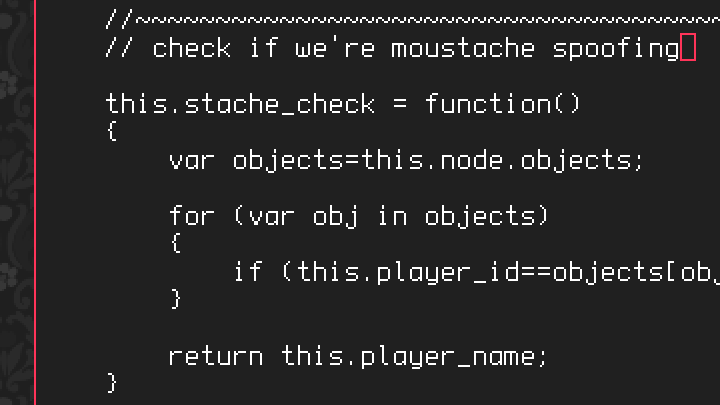

Dave: My thinking behind this approach came from a conversation with Maja Kuzmanovic at FoAM. We were discussing interventions of this type and the problems that come with a head on confrontation – that it creates publicity, a lot of ‘heat and light’ but doesn’t really encourage enough meaningful debate or further exploration. I consider one of the great strengths of this project was an avoidance of a simplistic message, we all use social networking, the corporations involved are simply following the logical conclusions of their business practices to satisfy their shareholders, and what is required is a much more informed debate on the issues involved. For these reasons it was vitally important that we strictly adhered to the rules of Facebook’s API use in relation to privacy (to do otherwise would have been deeply hypocritical) – it’s an open source project so the code can be audited, they had no technical or legal justification to act in our case.

Since it was created, Naked on Pluto has been presented in several exhibitions as an installation. How do you translate a web-based artwork that usually interacts with the user in the privacy of his home computer into an artistic environment in the context of a public show?

Marloes: We’ve exhibited the project in two different ways. At FILE 2012 for instance, Naked on Pluto was simply shown on a computer next to other works of net art. For this purpose we created a newspaper-style front page with reports from the game, so that when visitors are hesitant to log in to the game on a public computer using their Facebook account, they still get news from the game world via reports from SpyBots, ReporterBots and InterviewBots. At the ARCO exhibition in Madrid and the TEA Super Connect exhibition in Taipei we exhibited the project in installation form. The visitor would enter a dark library with light emitting books on the shelfs. The library plays a central role in the game and the installation was a physical representation of it. The space had EVr14 slogans printed on the shelves, books with logs of objects from the game world and everything that had happened to the object since the beginning of the game, peepholes in the walls and a projection of the game world on the floor showing all bots and players moving through the different spaces in the game and a few terminals where visitors could play the game. The whole set up evoked the feeling of being monitored by this big entity, Plutonian Corp.

Have you updated or modified the software in Naked on Pluto over the last two years? Do you consider it a work in progress?

Dave: Naked on Pluto has been the basis of lots of subsequent experiments, one of the biggest spin off projects was the FaceSponge Facebook livecoding system. This was a way to allow workshop participants to program with the Facebook API directly, and learn how to make their own social advertising software and search their friends data for interesting patterns, and share the programs they wrote with the other participants. This became one of the most effective ways to collaboratively explore the issues with online privacy. Outside of online privacy, the Naked on Pluto source code has gone on to form the basis for other work, such as SlubWorld – a collaboration between Alex McLean, Marloes and me – a collaborative musical online livecoding installation for Arnolfini in Bristol and Kunsthal Aarhus.

You made the code from Naked on Pluto freely available under a GNU Affero General Public License (AGPLv3). Do you know if it has been used to develop other projects (artistic or non-artistic)? You advocate the use of Free/Libre/Open Source Software (FLOSS) in the making of artistic projects. Which are the advantages of using this kind of software?

Aymeric: There are all sorts of reasons why you would like to distribute a work of art under a free culture license. However it is not necessarily as a hope that it will be used by other artists directly. Or said differently, artists releasing their work as a free culture expression should not expect that it will be used by other artists. If we look at free culture beyond the demagogical discourse of remix culture, putting our work with such a license is more of a statement about culture, and how the latter emerges from a constant appropriation of existing ideas and materials, rather than a means to provide the tools for others to make new projects. It can happen, of course, but this is something relatively rare outside of tightly linked collectives and closely related artistic practices, as Dave was pointing in his answer to the previous question. In that sense a free software art does not change the dynamics of cooperation and collaboration between artists. We also chose the AGPL, a copyleft license specifically geared towards server side applications, to highlight and contrast with the closed nature of the source code used by Facebook once we are passed the open and welcoming appearance of its developer documentation and API calls. As for the link with the tools that we use, I find that free software provide us with an autonomy, independence, and of course a potential for appropriation through direct modification of the source code, that is simply unmatched by closed source proprietary tools and formats. Whether this is something that can fit into any existing artistic practice or lead to a better art would be however a dubious statement to make. However, the question of empowerment, autonomy and production appropriation in the context of art and design is frequently overlooked. By being more clear and expressive about one’s practice, I hope that such discussions get more attention so as to not reduce the question of tools to the one of disposable apolitical things. Spoiler: they are not.

You have stated that “software is the artwork.” In your opinion, is the current development of new media art limited by what software developers are able or willing to provide?

Aymeric: Software can be approached as a medium. Here, I refer to two things: the medium as a communication device that can carry information, and the artistic medium that is the material used to make art. In both cases, it is obvious that the current state of software development, and technology in general, has a drastic impact on the aesthetics and the cultural context of so-called media art and all its branches. This limitation certainly is a constraint. Yet, art history has shown that constraints are possibly the most interesting catalyst for art creation. Next to that, this constraint is also a cultural one, in the sense that it can be used to address timely matters. For instance, in Naked on Pluto both aspects of the software as medium are expressed: we deliberately rely on Facebook software infrastructure to make a work that aims to communicate our concerns about Facebook itself.

Dave: Following up Aymeric’s analogy I think it’s hard to produce art with a medium that you don’t have a full understanding of, so I think it’s advantageous for artists working with software to learn some programming. This is not to say that we all have to be able to write our own software, but in terms of forming good working practice when collaborating, a literacy of what is possible – it’s greatly helped by a shared common understanding of the raw materials being used. Further to this, to a large extent I think this is true for everyone – as we move into a world where algorithms are increasingly deeply ingrained in our environment, programming – or more specifically a general ‘algorithmic literacy’ becomes an increasingly important life skill.

In the current overwhelming flow of information, everything is content. How can art stand out from this flow and, ideally, provide a reflection of what it means to live immersed in data?

Aymeric: Two approaches are possible: embracing or resisting. The first one is about engaging with the competitive process in which content is published, transformed and consumed online. The second one precisely aims at refusing to play such game, by making a counter-intuitive, counter-fashion one might say, use of media. Both require quick adaptation as whether they embrace or resist, they need to evolve with their cultural context. For instance, in the fist case, art must be very topical to become one with social media. One way to do it is by adopting the forms and modes of production of the latter, such as borrowing meme strategies so as to maximize visibility in social networks; or by overemphasizing gorgeous looking video documentation to be reproduced in trendy blogs and that will most likely be the only hyperreal part of the work with which most people will ever be able to engage with; or to simply work on top or against a specific popular web platform providing some sort net dialogue. At the opposite, to stand out is to simply refuse to engage with such matters, to develop more challenging aesthetics, in which case what you refer to as living immersed in data will become visible or questionable due to the absence of its cultural and technological context in the work. Of course what I am sketching here is a bit black and white, it is however the two extreme positions in which a work can deal with the self inflicted saturation of information and short attention span promoted for the best or the worst by all the software and hardware gadgets available today. That said, both strategies have downfalls. Resisting always come with the risk of being unable to engage with contemporary concerns, or even an audience, or instead, manages to do so within the walled gardens of an artistic intelligentsia. With Naked on Pluto, we are naturally more positioned in the first category and we’re already paying the consequences of being highly topical: from a technological perspective with the need to fight against the unavoidable obsolescence of the project against Facebook software changes, and from a cultural perspective as best exemplified with the recent Snowden’s revelations that turned out to be even more alienating than our satirical fiction, or any dystopian fictional work one could have thought of!

The use of bots in Naked on Pluto introduce the user to the increasingly common experience of interacting with seemingly intelligent machines. Will the future web become a sort of Elastic Versailles, a constant dialogue with artificially intelligent entities in a controlled environment?

Aymeric: Well, to some extent this is already the case. We’re quite far from the days where websites where just fully or semi manually formatted information sent by a server to a browser, and you could also go one step before to take into account the history of protocols such as gopher. Today, websites are essentially a mix of software running on the server and on the browser, and for all sorts of reasons, such software is trying to be clever and therefore it highly mediates the information we have access to. This has been explicitly demonstrated with the problem of filter bubble in search engines, namely how search engines tailor our search results based on our search habits. But of course this is not only specific to the web. Society as a whole has been increasingly relying on software assisted telecommunications for decades now. This form of assistance is growing as hardware improves and knowledge of computer science and engineering evolve. I think most people are still perceiving artificial intelligence as some very figurative thing, like a robot helping old people or an animated paperclip asking you if you want to run a spell checker on the resume you’re typing. In fact such representations, and their cultural context, of hardware and software technology are cursed by our desire to design useful anthropomorphic things. What happens instead is that so-called artificial intelligence implemented today is just a feature of some software that is necessary to make a task easier or a process more efficient and productive; the way it manifests itself is not connected to its nature and effects, let it be its interface. Practically speaking there is some artificial intelligence in all the gadgets we use, and it becomes increasingly difficult to keep track of what they do, how it manipulates us, and what happens when all these things start to interact with each others. This is probably why the openness of such things as well as their thorough peer-reviewing will become more and more essential in the years to come. But even then, even without talking about the speculative sentience of such things, the risks and abuses of technology can happen at so many different levels that transparency and analysis is not enough. This is to the point where I believe that we are more and more running towards a future where any basic technologically improved or assisted human activities will require an incredible leap of faith, otherwise denial … or some serious resilience.

Finally, how would you define artificial life?

Dave: Artificial life is a term that comes out of the remnants of artificial intelligence research in the eighties, and is concerned with a preference for emergent properties over planned ones – bottom up rather than top down design. A great deal of research was carried out in the nineties ‘growing’ software agents from populations of individuals, or studying how interactions between large numbers of simple organisms could result in complex behavior. The roots of this approach to design came from cybernetics, which is being increasingly scrutinized lately, as it is also the philosophical basis to the technology and networks that form the internet. Artificial life provided us with a consistent artistic approach to explore these kinds of issues, as Naked on Pluto is orchestrated by the interactions of a large number of independent agents, rather than a singular “grand plan”.

Aymeric: A thing that makes us wonder about our own existence and becoming.

Marloes: As “magic”, letting go of mastering, predicting and steering towards results and surrendering to anthropomorphism. Artificial life is the setting in motion of a series of automated processes that influence each other in such a way that their behavior becomes hard to predict, creating the illusion that they have a “life” of their own. A wonderful tool to tell stories about how we interact with technology.