My Lawyer is an Artist: Free Culture Licenses as Art Manifestos

UPDATE: New revised 2014 version here

Introduction

Most discussions around the influence of the free software philosophy on art tend to revolve around the role of the artist in a networked community and her or his relationship with so-called open source practices. Investigating why some artists have been quickly attracted to the philosophy behind the free software model and started to apply its principles to their creations is key in understanding what a free, or open source, work of art can or cannot do as a critical tool within culture. At the same time, avoiding a top down analysis of this phenomenon, and instead taking a closer look at its root properties, allows us to break apart the popular illusion of a global community of artists using or writing free software. This is the reason why a very important element to consider is the role that plays the license as a conscious artistic choice.

Choosing a license is the initial step that an artist interested in an alternative to standard copyright is confronted with and this is why before discussing the potentiality of a free work of art, we must first understand the process that leads to this choice. Indeed, such a decision is often reduced to a mandatory, practical, convenient, possibly fashionable step in order to attach a “free” or “open” label to a work of art. It is in fact a crucial stage. By doing so, the author allows her or his work to interface with a system inside which it can be freely exchanged, modified and distributed. The freedom of this work is not to be misunderstood with gratis and free of charge access to the creation, it means that once such a freedom is granted to a work of art, anyone is free to redistribute and modify it according to the rules provided by its license. There is no turning back once this choice is made public. The licensed work will then have a life of its own, an autonomy granted by a specific freedom of use, not defined by its author, but by the license she or he chose. Delegating such rights is not a light decision to make. Thus we must ask ourselves why an artist would agree to bind her or his work to such an important legal document. After all, works of art can already ‘benefit’ from existing copyright laws, so adding another legal layer on top of this might seem unnecessary bureaucracy, unless the added ‘paper work’ might in fact work as a form of statement, possibly a manifesto. In this case we must ask ourselves what kind of manifesto are we dealing with, what is its message? What type of works does it generate, what are their purpose and aesthetic?

The GNU manifesto

In the history of the creation and distribution of manifestos the role of printing and publishing is often forgotten or given a secondary role. But, what would have become of the Futurist Manifesto without the support of the printing press and the newspaper industry in France and the rest of Europe? Not much, probably. So it is not without irony that one of the anecdotes often given to illustrate the motivations of Richard Stallman to write the GNU Manifesto, the founding text behind the free software movement, is tightly linked to the story of a defective printer. Indeed, very often, the origin of the document starts with a story about a problem Richard Stallman and some colleagues of his faced when Xerox did not give away the driver source code of the printer they had donated to MIT, preventing the hackers at the lab to modify and enhance it to fit their specific needs. In this case, this particular printer model had the tendency to jam and the lack of feedback from the machine when it was happening made it hard for the users to know what was going on. [1] Beyond the inability to print, and behind what seems to be a trivial anecdote, this event still remains one of the best examples to illustrate the side effects proprietary software can have in terms of user alienation. The programmers and engineers that were using the printer could have fixed or found a workaround for the jamming, and contributed the solution to the company and other users. But they were denied the access to the source code of the software. Such a deadlock is one of the reasons why the GNU manifesto was written. What is unique in this manifesto, is the idea that software reuse and access should be enforced, not only because it belongs to a long history of engineering practice, but also because software has to be free.

Looking at the text itself, we can see that the tone and the writing style used by Stallman make the GNU Manifesto closer to an art manifesto, than to yet another programmer’s rant or technical guideline. As a matter of fact, we can read through the document and analyse it using the specific art manifesto traits that Mary Ann Caws has isolated based on the study of art manifestos produced during the twentieth century. [2] For instance Caws explains that “it is a document of an ideology, crafted to convince and convert.” This is

correct, the GNU manifesto starts with a personal story, turns it into a generalisation including other programmers and eventually involving the reader in the generalisation and explaining to her or him how to contribute right away. Caws also characterises the tone of manifestos as a “loud genre”, and it is not making a stretch to see this feature in the all-capital recursive acronym GNU and the way it is introduced to the reader. It is the first headline of the manifesto and sets the self-referential tone for the rest of the text, as well as embodying a permanent finger pointing to what it will never be: “What’s GNU? Gnu’s Not Unix!.” Furthermore, she reminds us that the manifesto “does not defend the status quo but states its own agenda in its collective concern”, which is what Stallman does with the use of headlines to announce the GNU road-map and intentions clearly: “Why I Must Write GNU,” “Why GNU Will Be Compatible with Unix,” “How GNU Will Be Available,” “Why Many Other Programmers Want to Help,” “How You Can Contribute,” “Why All Computer Users Will Benefit.” the GNU Manifesto also instructs its audience on how to respond to the document with the presence of a final section “Some Easily Rebutted Objections to GNU’s Goals” that lists and answers common issues that come to mind when reading it. Last but not least, manifestos are often written within a metaphorical framework that borrows its jargon from military lingo and for many the GNU Manifesto is being perceived and presented as a weapon, essential in the war against the main players of the proprietary software industry, such as Microsoft. In fact many hackers saw in the GPL an effective tool in “the perennial war against Microsoft.” [3] Thus, when the copyleft principle, the mechanism derived from the GNU manifesto, is introduced in the 1997 edition of the Stanford Law Review, it is precisely described as a “weapon against copyright” [4] and not just a ‘workaround’ or ‘hack’.

From the manifesto to the license…

This particular concept of freedom, as it is expressed in the manifesto, is focused on the usage and the users of software. It will eventually lead to the maintenance by the Free Software Foundation (FSF) of a definition of free software and the four freedoms that can ensure its existence. On top of that, the GNU Manifesto is practically implemented with the GNU General Public License (GPL), that provides the legal framework to enable its vision of software freedom. It means every work that is defined by its author as free software, must be distributed with the GPL. The license itself works as a constant reference to the manifesto, by the way it is affecting the software

and its source code distribution. Every software distributed with the GPL becomes the manifestation of GNU, and the license’s preamble is nothing else but an alternative text paraphrasing the GNU Manifesto. This preamble is not a creative addition to the license, on the contrary the Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) of the FSF even insists that it is an integral part of the license and cannot be omitted, thus making form and function coincide.

Even though the GPL was specifically targeting software, it does not take long for some people to see this as a principle that could be adapted or used literally in other forms of collaborative works. As early as 1997, copyleft is mentioned as a valid framework for collaborative artworks in which artists would pass “each work from one artist to another.” [5] Of course, this is suddenly brought to our attention not because of the collaboration itself, but because of its sudden legal validity. Indeed the idea of passing works from one

artist to another and encouraging derivative works is nothing new. For instance, back in the sixties, mail artists such as Ray Johnson even used the term “copy-left” in their work, [6] and it was possible on some occasions to spot the now very popular copyleft icon, an horizontally mirrored copyright logo, marking a mail art publication. In this context copy-left was seen as a symbol of “free-from-copyright relationships” with other artists in a way that was “not bound to ideologies”.[7] In a strange twist, the use of this term is echoing years later, not without cynicism, in some reproductions of Johnson’s works which are now stamped “Copyright the estate of Ray Johnson.”[8]

So why a sudden interest in such practices? Precisely because of the growing development of intellectual property in the field of cultural production. At the time, under the 1976 copyright act, the only recognised artistic collaborative work was the joint work, in which it is required that all the authors agree that all their contributions are meant to be merged into one, flattened down, work. This made perfect sense in the context of the print based copyright doctrine but was clearly not working for digital environments where the romantic vision of the author is dissolved in the complex network of branches, copies and processes inherent to networked collaboration. This

situation provided much headache to lawyers focused on the copyrighting of digitally born works. One of these works is for instance Bonnie Mitchell’s 1996 “ChainArt” project, in which her students and fellow artists were invited to modify a digital image and pass it to someone else using a file server. In such a project the whole process and its different iterations are the work itself, not the final image at the end of the chain. The work exists as a collection of derived, reused and remixed individual elements that cannot be flattened down into one single ‘joint work’ and as a consequence, from a legal perspective, could neither be protected nor credited properly under the limited copyright regulations.[9] No surprise then that Heffan picked the Chain Art project as an example of artistic work that could greatly benefit from the GPL and the use of copyleft that can encourage “the creation of collaborative works by strangers”.[10]

…and back to the manifesto

Although this conclusion makes perfect sense legally, it clearly overlooks and diminishes the artistic desire to reflect upon the nature of information in the age of computer networks. Many artists adopted the GPL early on, not because of their wish to collaborate with strangers, but instead to augment their work with a statement derived from the free software ideology. For instance Mirko Vidovic used the free software definition to develop the GNU Art project,[11] in which suddenly, the GPL becomes a political tag, a set of meta data that could be applied to any work of art. By choosing the GPL as a means of creation and distribution, artists are aiming at implementing an apparatus similar to the digital aesthetics that Critical Art Ensemble (CAE) had described “as a process of copying […] that offers dominant culture minimal material for recuperation by recycling the same images, actions, and sounds into radical discourse”.[12] The weapon against copyright becomes a flagship for the recombining dreams of the digital resistance as envisioned by CAE. But by directly reusing the GPL, projects such as GNU Art failed none the less to really break through the position of Stallman that refuses to take part in judging if whether or not works of art should be free.

This is why a few lawyers, Mélanie Clément-Fontaine, David Geraud, as well as artists, Isabelle Vodjdani and Antoine Moreau, felt the need to make more explicit the artistic context and motivations of a liberated work of art by creating the Free Art License (FAL), equivalent to the popular free software GNU public License and articulated specifically for the creation of free art. [13] Suddenly, the license becomes an art manifesto. In the FAL the rules of copyleft are exposed, they stand on their own and enable the artistic creation,

not for the sake of creating but as a means to produce singular and collective works. What is seen as freedom is just a very specific definition as envisioned in the GNU manifesto and that can only exist within the set of rules it represents. Moved to an artistic context, the rules to define freedom become a system to make art. In the same way that ‘cent mille milliards de poèmes’ was the 1961 OuLiPo manifestation of creative rules, the free art license is also a combinative manifesto, one that enables free art. It is not a simple adaptation of the GPL to the French copyright law, it is a networked art manifesto that operates within the legal fabric of culture.

Anyone who respects the rules of the FAL is allowed to play this game. Just like the ludic aspect in OuLiPo’s work, and its probable root from Queneau’s flirt with surrealism, artists who start to consciously use the GPL and the FAL solely for its ‘exquisite’ properties might start a superficial relationship with the creative process. Indeed, Raymond Queneau, co-founder of the OuLiPo reminded us already that we should not stop at the process’ aesthetics itself because “simply constructing something well amounts to reducing art to play, the novel to a chess game, the poem to a puzzle. Neither saying something nor saying something well is enough, it is necessary that it be worth saying. But what is worth saying? The answer cannot be avoided: what is useful.”[14] In other words and adapted to the FAL, the network aesthetics are not enough, their existence must be contextualised and positioned to escape its fate of a convenient technological and legal framework. This is why if the game aspect is obvious in the collective works that surround the FAL, we must see beyond the rules that are presented to us to perceive that such an artistic methodology aims to be an answer to the issue perceived by Chon in the analysis of the ChainArt project. Namely, to engage with the fluidity of information and try to turn the clichéd attitude of artists towards their unique and immutable contributions to art into a useful game. At the same time the emphasis is put on the collective nature of production and not community work.

The main issue with the intention of the FAL is that unlike the digital aesthetics modeled by CAE from Lautréamont’s ideas,[15] the mechanism of a free art, against the capitalisation of culture and for the free circulation of ideas within the network can only work by making the machine responsible for this very same capitalisation legitimate. While the mail art derivatives are happening outside of any obvious legal regulations, the copyleft art is literally hacking the system to reach a symbiosis and establish a kingdom within the kingdom. As a consequence these political works are very different from the artistic politics developed after the Russian revolution and World War I. Here, the artist is not an agent of the revolution but the vector of an ‘arevolution’. A copyleft art is in the end not so much a critical weapon but instead a cornucopia that operates recursively and only within the frame of its license. Artists that are engaging with it, thus turning the license in a shared manifesto, cannot materialise an anti-culture, a counter culture, nor a subculture, they must create their own from scratch. Instead of seeking opposition and destruction of an enemy, they aim at founding and building.

Conclusion

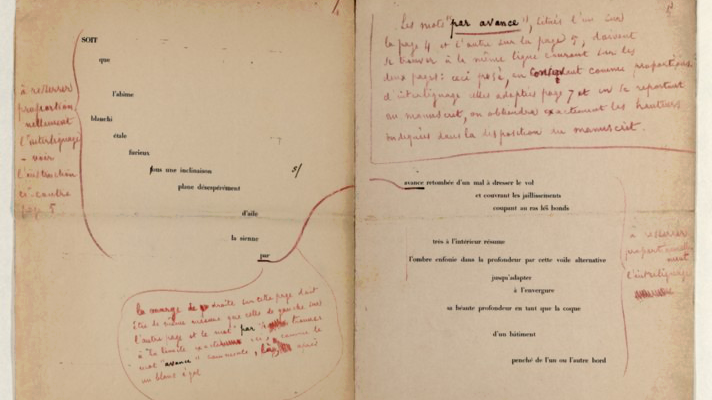

If we look at 1897 Mallarmé’s ‘Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard’, it is possible to only see it as an interesting visual design experiment in poetry. This approach misses the reason why this work exists in the first place. By turning art into the gathering and composing, even painting of both time and space within a text, it reached the apotheosis of parnassianism and symbolism upon which modernism broke through.[16] A similar issue of complex lineage and contextual information surrounds a document such as the FAL and leads to concurrent ‘raisons d’être.’ Indeed, the FAL is not just an ‘excercice de style,’ it is the embodiment of several elements that are announcing important changes in artistic practices: a call to turn legal rules into a constrained art system, a reflection on the nature of collaboration and authorship in the networked economy, a living archeology of the creative process by bringing traceability and transparency, and ultimately, the mark of an age of copyright and bureaucratic apotheosis that is pushing artists to develop their practice within the administrative structure of society and embed it in their creative process.

Unfortunately, and this is one of the reasons there is so much confusion and misunderstanding about the use of such licenses by artists and theoreticians, is that, with such a manifesto where form meets function, once the license is used, it triggers a process of rationalisation that leads to a fragmentation of the original ideology and intention into different, possibly contradictory, elements:

- A toolkit for artists to hack their practice and free themselves from consumerist workflows.

- A political statement against the transformation of the digital culture into what CAE calls the “reproduction and distribution network for the ideology of capital”.

- A legal and technical framework to interface with the current system and support existing copyright law practices.

- A lifestyle, and sometimes fashion statement.

In practice it is possible for an artist to only see one of these facets and either ignore or not be aware of the others, making the license as manifesto multidimensional, open to different interpretations, not unlike the medium it was drafted in: the law.

Footnotes

[1] Sam Williams, Free as in Freedom: Richard Stallman’s Crusade for Free Software, ed. Sam Williams (Sebastopol: O’Reilly and Associates, Inc., 2002).

[2] Mary Ann Caws, Manifesto: A Century of Isms (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000).

[3] Ibid. 1, p. 13.

[4] Ira V. Heffan, “Copyleft: Licensing Collaborative Works in the Digital Age,” in Stanford Law Review, Vol. 49, No. 6 (Jul., 1997), pp. 1487-1521.

[5] Ibid.

[6] “From Mail Art to Net.art (studies in tactical media #3)”, McKenzie Wark, email on the nettime mailing list, http://www.nettime.org/Lists-Archives/nettime-l-0210/msg00040.html.

[7] “RYOSUKE COHEN MAIL ART – ENGLISH”, accessed May 13, 2011, http://www.h5.dion.ne.jp/~cohen/info/ryosukec.htm.

[8] Ibid. 6.

[9] Margaret Chon, “New Wine Bursting from Old Bottles: Collaborative Internet Art, Joint Works, and Entrepreneurship,” in Oregon Law Review, Spring 1996.

[10] Ibid. 4.

[11] “GNUArt”, accessed May 13, 2011, http://gnuart.org.

[12] Critical Art Ensemble, “Recombinant Theatre and Digital Resistance,” in TDR (1988-), Vol. 44, No. 4 (Winter, 2000), pp. 151-166.

[13] “Free Art License 1.3,” accessed April 19, 2011, http://artlibre.org/licence/lal/en.

[14] Constantin Toloudis, “The Impulse for the Ludic in the Poetics of Raymond Queneau,” in Twentieth Century Literature, Vol. 35, No. 2 (Summer, 1989), pp.147-160.

[15] Ibid. 12.

[16] Jacqueline Levaillant, “Les avatars d’un culte: l’image de Mallarmé pour le groupe initial de la Nouvelle Revue Française,” in Revue d’Histoire littéraire de la France, 99e Année, No. 5 (Sept. -Oct., 1999), pp. 1047-1061.

Originally published in ISEA2011 proceedings