Licensing: copyright, legal issues, authorship, media work licensing, Creative Commons

Nicolas Malevé, November 2007

In this article, we will cover a few questions and principles of open content licensing. We will discuss why to use a license and how it helps to give a stable legal background to start a collaboration. As choosing a license means accepting a certain amount of legal formalism, we will see the conditions required to be entitled to use an open license. Using the comparison of the Free Art License and the Creative Commons, we will try to give an accurate picture of the differences that co-exist in the world of open licensing, and approach what distinguishes free from open licenses. We will end by envisioning briefly the case of domain specific licenses and with a more practical note on how to apply a license to a work.

Open Content Logos repository, by Femke Snelting [1]

Sharing your work

Let's assume you want to share your work. There may be many reasons to do that. You may want to have fun with others and see unexpected derivatives of your work. You may want to add to a video piece that you found on a website. You may have a band and you want to let your fans download your songs. You may be an academic and you are interested to see your writings circulate in different schools. There are as many reasons as there are people creating artworks and cultural artefacts. This variety is reflected in the ways people work together with each other. This article will discuss some of these ways, those which are characterised by the use of a open license.

Many collaborations happen informally. Your friends take one of your work and incorporate it in one of their works. You insert in your webpage a picture you found somewhere on the net. Someone else does the same with yours. Everything goes smoothly until someone suddenly disagrees. The audio file you sampled from your friend becomes a hit and he summons you to take it down from your webpage because he signed a contract. Someone didn't like the way you used his image on your blog and asks for removal. Whatever happens, if there is no formal agrement, the rule that will apply is the rule of copyright.

As the video maker, Peter Westenberg, sums it up in Affinity Video[2]:

"In this context it is worthwhile taking notice that ‘collaboration’ has a connotation of ‘working with the enemy', Florian Schneider writes in his text on the subject: “It means working together with an agency with which one is not immediately connected.” In order to make sure these people I don’t know, or don’t like, can actually copy, change and redistribute my work, I need to permit them to do so. If I do not, the copyright laws will be fully effective , and these laws might be too restrictive for what we want to achieve. I choose and attach an open license to my work, such as Creative Commons, Free Art License in the case of publishing media files, or the GPL General Public License in case of publishing software.

Counter to copyright, Free Licenses do not protect my exclusive rights of exploiting the object. They defend the rights of the object to be freely used and exploited by anybody, that is: including me. A license also helps me to protect me from what I want: which is applying trust, friendlyness, generosity and all other warm qualifications of personal relationships as if they were reliable protocols for exchange."

If not mentioned otherwise, your work is considered copyrighted, at least in the USA and most European countries. To open it for reuse or distribution, you need to make your intentions clear. To give warranty that you will not change your mind, to the people that will build on top of your work or re-distribute it, the easiest way to proceed is to chose a license. Using a work which is released under an open license gives you the insurance that the conditions under which it is released will not change. This license will list all the conditions under which you, the author, grant the rights to copy, distribute or modify your work as well as the duration of such an agreement. This license will list all the conditions under which you, the subsequent author, can use this work in your creations and will have consequences on the way you will release your own creation.

Open licenses help to clarify many things. This is why they must go along with the creative process. The choice of the license should be made early in the process of creation. If you plan to make a collaborative work or to base your work on someone elses, it is preferable to think about the conditions under which you will release your production. Choosing a license can help clarify the roles of the collaborators in a project, discuss each other expectations about its outcome and define the relationships of this work towards other works.

Finally, a license can be a very effective tool to counter the predatory behaviour of people using free material but unwilling to share the resulting work. Most of the open licenses include a clause that force people to share the subsequent work they produce under the same conditions as the material they used to create it. A license is a wonderful tool to keep available to the public the cultural material that belongs to it.

Going legal

Choosing a license means that you will formalise the way you want to share, collaborate. This means that you will have to enter (as briefly as possible) in the strange logic of lawyers.

Are you a 'valid' author?

This question sounds absurd. Why would some authors be more valid than others?

To be able to legally open your work to others, you need to be the 'valid' author of your work which means that you can't incorporate copyrighted material in your work. You can't use an open license to launder copyrighted material that you have borrowed elsewhere. If your creation has been made as part of your job, check if by contract your copyright doesn't belong to your employer, or if you haven't transfered your rights to anyone.[3] When it comes to open licensing, it is crucial to understand that you operate under the conditions of copyright, but you reformulate them. Open licenses propose a different use of copyright: they use the author's right to authorise, rather than to forbid.

Licenses

To authorize

The author's right is a right to authorise and prohibit. This authorisation can be negotiated subject to remuneration. An author can, for example, authorise, against financial compensation, the reproduction of its work, its audio-visual adaptation, etc. This practice is so widespread that many people amalgamate author's right and right of remuneration. The open licenses stress the possibilities for an author to authorise certain uses of its work free.

An open license:

- offers more rights to the user (the public) than the traditional use of the author's right. For example, the author can grant the free access to a work, can grant the right to redistribute it, to create derivative works.

- clarifies and defines the use which can be made of a work and under which conditions.

For example, the author can grant the free redistribution of his work, but only in a non-commercial use. Authorisation is given automatically for the uses which it stipulates. It is not necessary any more to ask the permission the author since its work is accompanied by an open licence.

Open and Free

Until now in this text we only talked about open licenses. It is time now to make an important difference. Open means a 'less restrictive' license than default copyright. It englobes licenses which grant quite different types of permissions. Some licenses, however, are described as free. The use of the term free as in free software[4] or free license has a very specific meaning. A software that is free, aka copyleft, must give the user the following rights:

1. the freedom to use and study the work,

2. the freedom to copy and share the work with others,

3. the freedom to modify the work,

4. and the freedom to distribute modified and therefore derivative works.

And the license has to ensure that the author of a derived work can only distribute such works under the same or equivalent license.

Typically, if a developper wants to make his/her software free (instead of open), he or she will choose the Gnu GPL [5], a license that grants and secures these rights. A free license for creative content will therefore grant the same rights to other creators.

1 the freedom to use the work and enjoy the benefits of using it

2 the freedom to study the work and to apply knowledge acquired from it

3 the freedom to make and redistribute copies, in whole or in part, of the information or expression

4 the freedom to make changes and improvements, and to distribute derivative works

As stated on the freedomdefined.org website [6]: "These freedoms should be available to anyone, anywhere, anytime. They should not be restricted by the context in which the work is used. Creativity is the act of using an existing resource in a way that had not been envisioned before."

This distinction between free and open is not only a political one but also has important practical consequences. To approach these differences we will compare two important types of licenses that are used by many artists and creators, the Free Art License and the Creative Commons licenses.

The Free Art License

The Free Art License (FAL) [7] was drawn up in 2000 by Copyleft Attitude, a French group made of artists and legal experts. The goal was to transfer the General Public License to the artistic field. In the GPL, Copyleft Attitude was looking for a tool of cultural transformation and an effective means to help disseminate a piece of work. The world of art was perceived as being entirely dominated by a mercantile logic, monopolies and the political impositions deriving from closed circles. Copyleft Attitude tried to seek out a reconciliation with an artistic practice which was not centred on the author as an individual, which encouraged participation over consumption, and which broke the mechanism of singularity that formed the basis of the processes of exclusion in the art world, by providing ways of encouraging dissemination, multiplication, etc. From there on, the FAL faithfully transposes the GPL: authors are invited to create free materials on which other authors are in turn invited to work, to create an artistic origin from which a genealogy can be opened up.

The FAL shares with the GPL the project of re-examining the existing terms of the relations between individuals and access to creation and artworks. The FAL does include elements of great interest from an egalitarian point of view between the creators who use them. The position of the different authors in the chain of works does not consist of a hierarchy between the first author and a subsequent one. Rather, the licence defines the subsequent works as original works "resulting from modification of a copy of the original work or from modification of a copy of a consequent work", and throughout the text of the license they are mentioned regularly. This concern has left its mark on various of the group's practices and, of course, on the license logo -- of which there are as many different versions as there are interested users.

Creative Commons

Set up in 2001 by an essentially academic group (legal experts, scientists, employers and a director of documentaries) and backed by one foundation and several universities, the Creative Commons (CCs)[8] acknowledged that their inspiration came from the GPL. However, they are more influenced by the pragmatic potential (how to solve a problem) of the GPL than by its potential to transform. In effect, the CCs present themselves as the "guarantors of balance, of the middle ground and of moderation". Unlike the GPL, which is a specific mechanism for effecting a modification in the system of creation/dissemination of software, the CCs have been set up to smoothen it out, make it more flexible, more moderate, although not entirely different. The main aim is to save the cost of a legal transaction when drawing up a contract, and to restore the friendly image of the Internet - which has been turned into a battlefield with the growing number of lawsuits against Internauts - in order to restore confidence among possible investors.

What the CCs propose is a palette of licenses that offer the possibility of granting users certain rights. These rights may be more limited than those awarded by the GPL and the FAL. Users of the CCs can choose between authorising or prohibiting modification of their work, commercial use of their work and a possible obligation to re-distribute the subsequent work under the same conditions. In the CCs, two distinctions are re-introduced which were not contained in the GPL: the possibility of prohibiting modification of a work and the difference between commercial and non-commercial use. The CCs give the author a predominant position. He or she can decide whether to authorise the subsequent use of the work, and is defined as the original author. When this decision is taken, the authors can request that their names not be associated with a derived work whose contents they do not approve of. If the GPL excludes the commercial/non-commercial distinction (the user is given the freedom to sell the software), it is because the possibility of trading with the resulting code will help accelerate its propagation. The greater the propagation, the greater the dissemination achieved by the free software and the greater the number of monopolies that will be abolished. The business made from a piece of free software is simply considered as another means of propagation.

The GPL (and the FAL) is a license that is monolithic. All the programmers that use the GPL grant the same rights and respect the same rules. Even if they do not know each other, the programmers who use the GPL form a community. This is not the case for the Creative Commons licenses. They are conceived as modular tools for renegotiating individual contracts, based on individual relations. Naturally, we can use the CCs to create a license close to the FAL/GPL; accepting the transformations and commercial use, on condition that the author is mentionned and that these conditions are applied to subsequent works. But this is just one of the possibilities on offer. As tools, these licenses logically anticipate the varieties of conflicts which might arise with the use of the work as a commercial reappropriation or the deformation/de-naturalisation of a text or a film. The CCs don't decide for you what kind of freedom you want to give to the people who would like to access, play with, modify or redistribute your work. They give you the tools to specify these conditions yourself in a form that is legally recognised.

Domain specific licenses

As we said in the introduction, there are many ways one might like to share their work. Many important licenses have been dedicated to specific areas of artistic/cultural production.[9] You can find licenses dedicated to music, to documentation, etc. As these licenses are specific to a domain, they may contain very precise constraints that are absent to general-purpose licenses. Therefore they require careful attention because they may include particular clauses.

The case of the GNU Free Documentation License.

The GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL) [10] is used by one of the most important projects of free culture: wikipedia[11]. Originally, the GFDL has been conceived to:

"make a manual, textbook, or other functional and useful document "free" in the sense of freedom: to assure everyone the effective freedom to copy and redistribute it, with or without modifying it, either commercially or noncommercially. Secondarily, this License preserves for the author and publisher a way to get credit for their work, while not being considered responsible for modifications made by others.

This License is a kind of "copyleft", which means that derivative works of the document must themselves be free in the same sense. It complements the GNU General Public License, which is a copyleft license designed for free software."

With the rise of Wikipedia, one can easily imagine making a series of publications based on this rich pool of articles. It is however, very important to read the license carefully since it requires from the publisher a series of extra references and constraints if more than 100 copies are to be printed. Extra precautions are also required if one agregates (mix GFDL licensed texts with others) or modifies the original text.

How to apply a license to your work?

Every license has a website that will give the correct information to help you add the license information regarding your work. Most of them will give you a small piece of text to include in place of the copyright notice, that refers to the full text of the license for in-depth information. Others provide a tool to generate the license info and the links in the format you need (HTML if you need to include in your blog, text format, logos, etc). Additionally, they will create for you a version that will be easily readable for search engines in a standard format called RDF[12]. We will call all these informations related to the license: license metadata[13]. Many platforms on the web that help publish media (Flickr, blip.tv etc) will offer interfaces to select a license and generate the links to their official documents. Your favourite image or sound editing software may assist you in creating the license metadata. And last but not least, search engines may help your work to be found according to the criteria you have chosen in your license.

Doing it by hand

In all cases, you can include the license information manually. First check the official website of your chosen license. You will find there a small piece of legal text that you will have to include next to your creation. As well as tips on how to explain to other people what this legal information means to them.

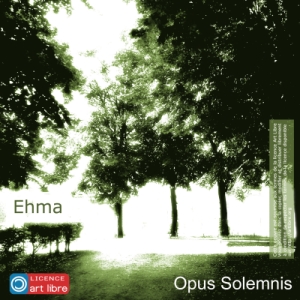

For example, if you publish an audio-CD under the Free Art License, you will include this information on the cover [10]:

[- A few lines to indicate the name of the work and to give an idea of what it is.]

[- A few lines to describe, if necessary, the modified work of art and give the name of the author/artist.]

Copyright © [the date] [name of the author or artist] (if appropriate, specify the names of the previous authors or artists)

Copyleft: this work of art is free, you can redistribute it and/or modify it according to terms of the Free Art license.

You will find a specimen of this license on the site Copyleft Attitude http://artlibre.org as well as on other sites.

It is usually a good idea to explain what this license authorises in a few lines in your own style:

You can copy the music on this CD, make new creations with it and even sell them as you want, but you need to give credit to the author and to share the creations you made with this work under the same conditions.

CD cover of the artist Ehma

Above is an example of a CD cover of the artist Ehma [15]. He mentions (bottom left of the image) the type of license he has chosen and more discretely (at the right-hand side), he gives a small description of what you can do with the music and where to find the complete text of the license.

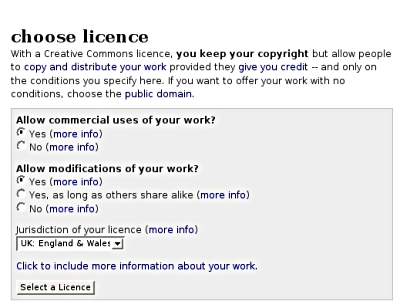

Using Creative Commons license generator.

If you say: "my work is released under a Creative Commons license" it doesn't tell much about what one can or can't do with the work. It is only when one knows if commercial use is granted or if modification is allowed that the license starts to make sense. To make it easier to understand at first sight, Creative Commons produced a series of logo to be put next to the work. Different formats for the same licenses can also be easily produced from the website and links provided to different references documents (the human readable version, the lawyer-redable version and the machine readable version, the one you will use for search engines, ie). The generation of all these documents and their related links is done via a web interface.

The license generator of Creative Commons website

For example, let's imagine that you want to publish your photos on your website under a license that allows others to copy, modify, but restricts commercial use and obliges them to share their subsequent work under the same conditions. Going on the creativecommons website, in the "publish your work" section [16], a page will offer you the many options you need to specify the conditions under which you want to publish your work. Once your options are selected, a snippet of html code is provided. You just need to include it in your website next to your photos.

a few examples of Creative Commons logos

Creative Commons put a lot of effort in finding solutions to make it easy to generate license metadata but also to give intuitive symbols explaining what you can do with the artwork. Each condition of use is represented by a logo. A combination of these logos acts as a visual summary of your choices regarding your work.

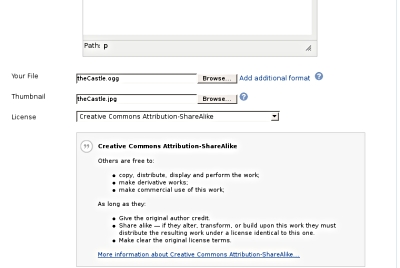

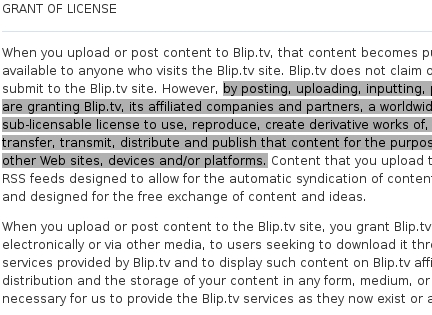

Using a sharing platform (be cautious!)

If you are a user of a sharing platform like Flickr.com, blip.tv or others, you will be asked to specify the conditions under which you want your work to be distributed. Each of these websites have an easy interface to let you select the appropriate license and automatically generate the reference to the official license text. Beware: if you use one of these services, read their terms of use carefully. Usually they will ask you, before using their service, to agree on a specific set of conditions regarding your copyrights and the use they, as a company (or their affiliates), can make of the works you publish on their platform. These conditions may vary strongly. You have to understand that when you use these platforms, you have to make two licenses. One between you and the platform, that will be dictated by its terms of use and validated when you click on the button "I agree". And a second one between you and the users/visitors of this platform, that can be a license of your choice, selected when you upload your file on the platform. If you use this platform to redistribute the work of someone else (as many open licenses allow you to do) or to publish derivative works (as many open licenses allow you to do), be careful that the terms of use (the contract between you and the platform) are not in contradiction with the license of the work you want to redistribute or publish.

Select a Creative Commons license on Blip.tv

Sample from Terms of service document from Blip.tv

In the example above, a user subscribed to the blip.tv [17] service may choose between full copyright, public domain and several variations of the Creative Commons. But to access such a service, the user has already accepted the terms of use of blip.tv that specify that s/he accepts that blip.tv may reproduce, create derivative works and redistribute her/his videos on blip.tv and affiliated websites. At this point, it is really important to pay attention to potential contradictions.

For instance, if you want to post a video from someone else who accepts that his/her video to be redistributed but not transformed, you can't post it to blip.tv: his/her licensing choice and blip.tv's terms of use are in contradiction. You can't accept for him/her that blip.tv makes derivative work from his/her video. Another problem comes from the non-commercial clause of the Creative Commons licenses. If you want to publish a video based on the work of someone else's footage and if this footage is released under a non-commercial CC license, be extra-careful about what you accept regarding advertising in the terms of service. Usually the platforms reserve the right of placing advertisements in the pages where they show your content and because Creative Commons doesn't define exactly is meant by "non-commercial" [18], you may enter a grey zone. Be even more careful if you chose a formula in which the platform proposes you to share the revenues on advertisements placed in your video or next to it.

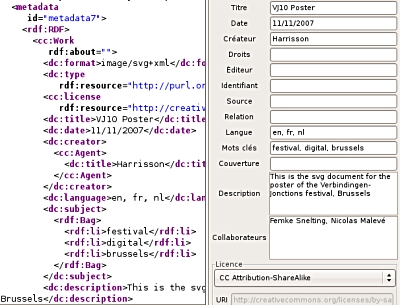

Metadata from your favourite editor

Many tools that help you create content may also help you insert license metadata. For writers, Creative Commons propose add-ons that allows license information to be embedded in OpenOffice.org Writer, Impress and Calc documents. For weblogs as Wordpress, a plugin called Creative-Commons-Configurator [19] provides the blog owner with the ability to set a Creative Commons License for a WordPress [20] blog and control the inclusion or display of the license information into the blog pages or the syndication feeds.

Inkscape, the metadata editor and the code it produces.

The screenshot above shows the example of the Inkscape [21] vector graphic editor. In the menu preferences, if you select the tab "metadata", you will be presented a series of fields to describe your image and a menu that will allow you to select among many licenses (not just Creative Commons). The result is a standard metadata embedded in the code of the image and ready to be parsed by search engines if you post it on the web.

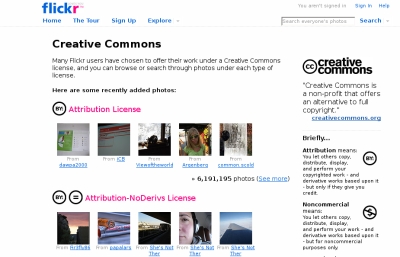

Be found

One of the benefits of using the tools proposed by Creative Commons is that it will help the search engines to "understand" the kind of uses you grant to the internauts.

Flickr, search by type of license [22].

Therefore, Yahoo, Google, Flickr and other search engines or services allow their users to make queries with specific filters: ie, Search only pages that are free to use or share, even commercially. They will then list only results that match these particular permissions.

This text has only scratched the surface of open content licensing. We hope that we have clarified a few important principles and given useful starting points. Nothing, however, will replace your own experience.

Notes

[1] http://www.constantvzw.com/downloads/posterOCL.pdf

[2] http://osvideo.constantvzw.org/?p=97

[3] Creative Commons made a list of things to think about before chosing a license: http://wiki.creativecommons.org/Before_Licensing

If you are a member of a collecting society, good chances are that you will not be allowed to use free licenses since you transfered your rights management to it. Check with them if any compromise can be found.

[4] http://www.gnu.org/philosophy/free-sw.html

[5] Freshmeat that "maintains the Web's largest index of Unix and cross-platform software, themes and related "eye-candy"" provides statistics of the referenced projects: more than 63 % of these projects are released under the Gnu GPL. http://freshmeat.net/stats/

[6] http://www.freedomdefined.org/Definition

[7] http://artlibre.org/licence/lal/en/

[8] http://www.creativecommons.org

[9] For more development on domain specific licenses, check the fourth chapter of the Open Licenses Guide, by Lawrence Liang published on the website of the Piet Zwart Institute: http://pzwart.wdka.hro.nl/mdr/research/lliang/open_content_guide/05-chap...

[10] http://www.gnu.org/licenses/fdl.html[11] http://www.wikipedia.org

[12] Rdf, Resource Description Framework, general method of modeling information, through a variety of syntax formats. See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Resource_Description_Framework

[13] Metadata simply means data about data. See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metadata#Image_metadata

[14] http://artlibre.org/licence/lal/en/ see bottom of the page, FAQ.

[15] Ehma, http://www.jamendo.com/en/artist/ehma

[16] http://a3-testing.creativecommons.org/license/

[17] http://blip.tv/

[18] There are a lot of questions concerning the use of the non-commercial clause in the Creative Commons licenses. The CC website anounces that:" In early 2008 we will be re-engaging that discussion and will be undertaking a serious study of the NonCommercial term which will result in changes to our licenses and/or explanations around them." http://wiki.creativecommons.org/NonCommercial_Guidelines

[19] http://www.g-loaded.eu/2006/01/14/creative-commons-configurator-wordpres...