Software art

Olga Goriunova, September 2007

The term ‘software art’ acquired a status of an umbrella term for a set of practices approaching software as a cultural construct. Questioning software culturally means not taking for granted, but focusing on, recognising and problematising its distinct aesthetics, poetics and politics captured and performed in its production, dissemination, usage and presence, contexts which software defines and is defined by, histories and cultures built around it, roles it plays and its economies, and various other dimensions. Software, deprived of its alleged ‘transparency’, turns out to be a powerful mechanism, a multifaceted mediator structuring human experience, perception, communication, work and leisure, a layer occupying central positions in the production of digital cultures, politics and economies.

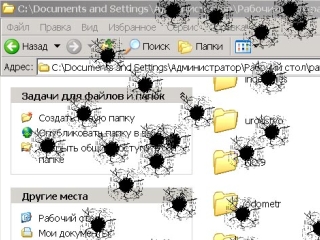

gun.exe by Anonymous

The history of framing ‘software art’ allowed for inclusion of a wide variety of approaches, whether focused on code and its poetics, or on the execution of code and art generated ‘automatically’, or on the visual-political aesthetics of interfaces and ‘languages’ of software, or on the traditions of ‘folklore’ programmers’ and users’ cultures creation, use and misuse of software, or on software as a ‘tool’ of social and political critique and as an artistic medium, even perceived within the most traditionalist frameworks, and many more. ‘Genres’ of software art may include text editors that challenge the culture of writing built into word processing software and playfully engage with the new roles of words, all indexed in the depths of search engine databases; browsers, critically engaging with the genre of browser software as a culturally biased construct that wants to both trigger and control users’ perceptions, ideas and desires; games, rebelling against chauvinist, capitalist, military logic encoded into commercial games and questioning the seeming “normality” of game worlds; low-tech projects based on creative usage of limited, obsolete algorithms; bots as pieces of software that, like normal bots, crawl the web in gathering information or perform other tasks, but, unlike them, reveal hidden links, perform imaginative roles and work against normative functions; artistic tools working towards providing new software models for artistic expression and rich experience, sometimes made in spite of mainstream interface models; clever hacks, deconstructions or misuse of software; projects providing environments for social interactions, including non-normative, or looking at the development of software as a social praxis, and many others, complex enough or too elegantly simple to be locked into the framework of a single ‘genre’[1].

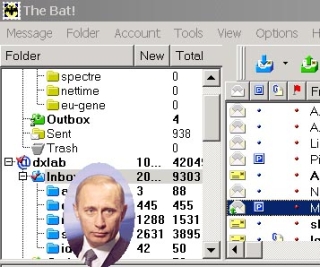

Portrait of the President (putin.exe) by Vladislav Tselisshev

Software art as a term appeared around the late 1990's from net art discourse[2]. Interest in the code of Internet web-pages and the functioning of networks, characteristic of net art, developed towards problematising software running Internet servers and personal computers, towards different kinds of software behind any image, process, instrument or channel[3].

Since software can be defined as a set of formal instructions that can be executed by a computer, or as code and its execution at the same time[4], a history of precursors of software art, including permutational poetry, Dada and Fluxus experiments with formal variations and, especially, conceptual art based on execution of instructions, can be retrospectively built[5].

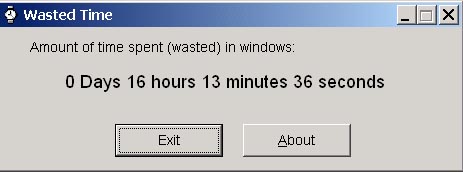

Wasted time by Anonymous

Software art’s relation to net art and art history does not exhaust its ‘roots’ and scope of approaches in a historical context. One of the forces of software art lies in its capitalization on the grass-roots traditions of programmers’ and users’ cultures of software creation and usage, some ‘digital folklore’, and in its references to more specific traditions, such as demo (a multimedia presentation computed in real time and used by programmers to compete on the level of the best programming graphic and music skills, originating from the hackers’ scene of the early 1980's, when short demos were added to the opening visuals of cracked video games) and some other powerful and old traditions, such as generative art, rooted in both artistic and programmers’ cultures.

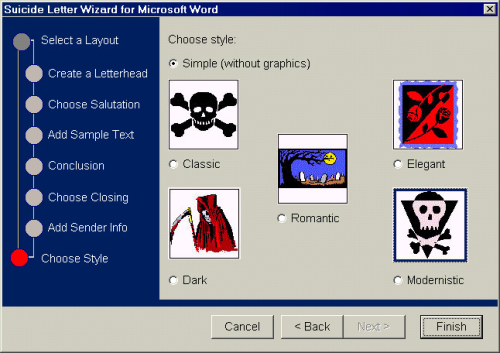

Suicide Letter Wizard for Microsoft Word by Olga Goriunova

Since the 1950's (when the first high-level programming languages were created and when the first mainframe computers were bought by a few large universities) smart and funny uses of technology, entertaining games, code poetry contests, fake viruses and other forms have been building up cultures of ‘digital folklore’: ‘… there is the field of gimmicks, nerdy tricks and playing with the given formulas, the eyes which follow the mouse pointer. … there is the useless software production, insider gags, Easter eggs, hidden features based on mathematical jokes, the Escher - trompe-l'oeil effects of playing with perception…’[6] Digital folklore exists in relation to a group of programmers, designers or informed users worldwide; it embeds, and is embedded within, codes of behaviour, of relations to employers and customers, to users, colleagues and oneself; it is correlated with the most important institutes, repeated actions, situations, models and is often based on non-formal means of production, dissemination and consumption. The variety of software cultures rooted in ‘geek’ practices, traditions of ‘bedroom’ cultures, cultures of software production and patterns of usage and adjustment build up sources of inheritance and inspiration for software art along with activist and artist engagements with software, each with histories of their own.

Software art benefited from currents of interest of more academic nature in the cultural and socio-political contexts of technology and, precisely, software[7]. The current form and ‘state’ of software art is due to a particular history of institutional development[8]. There also could be named a number of projects, practices and discourses conceptually and practically close to what is termed ‘software art’, which chose or happened to distance themselves from the usage of this term and from its institutional incarnations, for their potentially ‘limiting’ character in linking it to specific art fields, histories, and agents[9]. Moreover, departing from the term ‘software art’ might allow for starting up new stories and making visible some undervalued and overlooked practices and approaches.

Notes

[1] The above-mentioned ‘genres’ are taken from Runme.org software art repository’s ‘taxonomy’ that includes more categories than listed and presents one of the attempts to be open to a wide variety of approaches by building contradictory and, to a degree, self-evolving classificatory ‘map’ of software art.

[2] One of the first written mentionings of the term ‘software art’ can be found in Introduction to net.art (1994-1999) by Alexei Shulgin and Natalie Bookchin; http://easylife.org/netart/

[3] Deconstructions of HTML by Jodi, for instance, turned into the modification of old computer video game Wolfenstein 3D - SOD (1999) and other games. Projects such as alternative web browsers that were considered part of the net art movement started to be written back in 1997 with Web Stalker by I/O/D, continued by Web Shredder by Mark Napier in 1998, and Netomat by Maciej Wisniewski in 1999, and often got labeled as ‘online software art’.

[4] Cramer, Florian. Concept, Notation, Software, Art. 2002; http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~cantsin/homepage/writings/software_art/con...

[5] Ibid. See also: Cramer, Florian and Gabriel, Ulrike. Software Art. 2001; http://www.netzliteratur.net/cramer/software_art_-_transmediale.html and Albert, Saul. Artware.1999. Mute, Issue 14, London. http://twenteenthcentury.com/saul/artware.htm

[6] Schultz, Pit. Interviewed by Alexei Shulgin. Computer Age is Coming into Age. 2003. http://www.m-cult.org/read_me/text/pit_interview.htm

[7] It is difficult and lengthy to enumerate all the interesting publications on the issue. An excellent example is Software Studies: a Lexicon. Ed. by Matthew Fuller, 2008, Cambridge, The MIT Press.

[8] Transmediale, Berlin-based media art festival introduced an ‘artistic software’ category in 2001 (ran until 2004), Readme software art festivals (2002-2005) and Runme.org software art repository (running from 2003) added on to the construction of the current ‘layout’ of ‘software art’ if it is taken as a scene defined institutionally. The list of events is continued by exhibitions, such as I love you [rev.eng] (Museum of Applied Arts Frankfurt, 2002; (http://www.digitalcraft.org/iloveyou/), Generator (Liverpool Biennale, 2002; http://www.generative.net/generator/), CODeDOC (Whitney Museum, NY, 2002; http://artport.whitney.org/commissions/codedoc/index.shtml), and a number of symposiums, conferences and discussions.

[9] Matthew Fuller, for instance, suggested ‘critical software’, ‘social software’ and ‘speculative software’ as generic titles for practices software art attempted to draw in; see: Fuller, Matthew. Behind the Blip, Software as Culture. (some routes into “software criticism”, more ways out). 2002. In: Fuller, Matthew. Behind the Blip. Essays on the Culture of Software. 2003, New-York, Autonomedia.

Images

[1] gun.exe by anonymous

[2] Portrait of the President (putin.exe) by Vladislav Tselisshev, image courtesy of the author

[3] Wasted time by anonymous

[4] Suicide Letter Wizard for Microsoft Word by Olga Goriunova, image courtesy of the author

$(echo echo) echo $(echo): Command Line Poetics

Florian Cramer, 2003 / 2007

Design

Most arguments in favor of command line versus graphical user interface (GUI) computing are flawed by system administrator Platonism. A command like "cp test.txt /mnt/disk" is, however, not a single bit closer to a hypothetic "truth" of the machine than dragging an icon of the file.txt with a mouse pointer to the drive symbol of a mounted disk. Even if it were closer to the "truth", what would be gained from it?

The command line is, by itself, just as much an user interface abstracted from the operating system kernel as the GUI. While the "desktop" look and feel of the GUI emulates real life objects of an analog office environment, the Unix, BSD, Linux/GNU and Mac OS X command line emulates teletype machines that served as the user terminals to the first Unix computers in the early 1970s. This legacy lives on in the terminology of the "virtual terminal" and the device file /dev/tty (for "teletype") on Unix-compatible operating systems. Both graphical and command line computing are therefore media; mediating layers in the cybernetic feedback loop between humans and machines, and proofs of McLuhan's truism that the contents of a new medium is always an old medium.

Both user interfaces were designed with different objectives: In the case of the TTY command line, minimization of typing effort and paper waste, in the case of the GUI, use of - ideally - self-explanatory analogies. Minimization of typing and paper waste meant to avoid redundancy, keeping command syntax and feedback as terse and efficient as possible. This is why "cp" is not spelled "copy", "/usr/bin/" not "/Unix Special Resources/Binaries", why the successful completion of the copy command is answered with just a blank line, and why the command can be repeated just by pressing the arrow up and return keys, or retyping "/mnt/disk" can be avoided by just typing "!$".

The GUI conversely reinvents the paradigm of universal pictorial sign languages, first envisioned in Renaissance educational utopias from Tommaso Campanella's City of the Sun to Jan Amos Comenius illustrated school book "Orbis Pictus". Their design goals were similar: "usability", self-explanatory operation across different human languages and cultures, if necessary at the expense of complexity or efficiency. In the file copy operation, the action of dragging is, strictly seen, redundant. Signifying nothing more than the transfer from a to b, it accomplishes exactly the same as the space in between the words - or, in technical terms: arguments - "test.txt" and "/mnt/disk", but requiring a much more complicated tactile operation than pushing the space key. This complication is intended as the operation simulates the familiar operation of dragging a real life object to another place. But still, the analogy is not fully intuitive: in real life, dragging an object doesn't copy it. And with the evolution of GUIs from Xerox Parc via the first Macintosh to more contemporary paradigms of task bars, desktop switchers, browser integration, one can no longer put computer-illiterate people in front of a GUI and tell them to think of it as a real-life desk. Never mind the accuracy of such analogies, GUI usage is as much a constructed and trained cultural technique as is typing commands.

Consequentely, platonic truth categories cannot be avoided altogether. While the command line interface is a simulation, too - namely that of a telegraphic conversation - its alphanumeric expressions translate more smoothly into the computer's numeric operation, and vice versa. Written language can be more easily used to use computers for what they were constructed for, to automate formal tasks: the operation "cp *.txt /mnt/disk" which copies not only one, but all text files from the source directory to a mounted disk can only be replicated in a GUI by manually finding, selecting and copying all text files, or by using a search or scripting function as a bolted-on tool. The extension of the commmand to"for file in *; do cp $file $file.bak; done" cannot be replicated in a GUI unless this function has been hard-coded into it before. On the command line, "usage" seamlessly extends into "programming".

In a larger perspective, this means that GUI applications typically are direct simulations of an analog tool: word processing emulates typewriters, Photoshop a dark room, DTP software a lay-out table, video editors a video studio etc. The software remains hard-wired to a traditional work flow. The equivalent command line tools - for example: sed, grep, awk, sort, wc for word processing, ImageMagick for image manipulation, groff, TeX or XML for typesetting, ffmpeg or MLT for video processing - rewire the traditional work process much like "cp *.txt" rewires the concept of copying a document. The designer Michael Murtaugh for example employs command line tools to automatically extract images from a collection of video files in order to generate galleries or composites, a concept that simply exceeds the paradigm of a graphical video editor with its predefined concept of what video editing is.

The implications of this reach much farther than it might first seem. The command line user interface provides functions, not applications; methods, not solutions, or: nothing but a bunch of plug-ins to be promiscuously plugged into each other. The application can be built, and the solution invented, by users themselves. It is not a shrink-wrapped, or - borrowing from Roland Barthes - a "readerly", but a "writerly" interface. According to Barthes' distinction of realist versus experimental literature, the readerly text presents itself as linear and smoothly composed, "like a cupboard where meanings are shelved, stacked, safeguarded".1 Reflecting in contrast the "plurality of entrances, the opening of networks, the infinity of languages",2 the writerly text aims to make "make the reader no longer a consumer, but a producer of the text".3 In addition to Umberto Eco's characterization of the command line as iconoclastically "protestant" and the GUI as idolatrously "catholic", the GUI might be called the Tolstoj or Toni Morrison, the command line the Gertrude Stein, Finnegans Wake or L.A.N.G.U.A.G.E poetry of computer user interfaces; alternatively, a Lego paradigm of a self-defined versus the Playmobil paradigm of the ready-made toy.

Ironically enough, the Lego paradigm had been Alan Kay's original design objective for the graphical user interface at Xerox PARC in the 1970s. Based on the programming language Smalltalk, and leveraging object oriented-programming, the GUI should allow users to plug together their own applications from existing modules. In its popular forms on Mac OS, Windows and KDE/Gnome/XFCE, GUIs never delivered on this promise, but reinforced the division of users and developers. Even the fringe exceptions of Kay's own system - living on as the "Squeak" project - and Miller Puckette's graphical multimedia programming environments "MAX" and "Pure Data" show the limitation of GUIs to also work as graphical programming interfaces, since they both continue to require textual programmation on the core syntax level. In programmer's terms, the GUI enforces a separation of UI (user interface) and API (application programming interface), whereas on the command line, the UI is the API. Alan Kay concedes that "it would not be surprising if the visual system were less able in this area [of programmation] than the mechanism that solve noun phrases for natural language. Although it is not fair to say that `iconic languages can't work' just because no one has been able to design a good one, it is likely that the above explanation is close to truth".4

Mutant

CORE CORE bash bash CORE bash

There are %d possibilities. Do you really

wish to see them all? (y or n)

SECONDS

SECONDS

grep hurt mm grep terr mm grep these mm grep eyes grep eyes mm grep hands

mm grep terr mm > zz grep hurt mm >> zz grep nobody mm >> zz grep

important mm >> zz grep terror mm > z grep hurt mm >> zz grep these mm >>

zz grep sexy mm >> zz grep eyes mm >> zz grep terror mm > zz grep hurt mm

>> zz grep these mm >> zz grep sexy mm >> zz grep eyes mm >> zz grep sexy

mm >> zz grep hurt mm >> zz grep eyes mm grep hurt mm grep hands mm grep

terr mm > zz grep these mm >> zz grep nobody mm >> zz prof!

if [ "x`tput kbs`" != "x" ]; then # We can't do this with "dumb" terminal

stty erase `tput kbs`

DYNAMIC LINKER BUG!!!

Codework by Alan Sondheim, posted to the mailing list "arc.hive" on July 21, 2002

In a terminal, commands and data become interchangeable. In "echo date", "date" is the text, or data, to be output by the "echo" command. But if the output is sent back to the command line processor (a.k.a. shell) - "echo date - sh" - "date" is executed as a command of it own. That means: Command lines can be constructed that wrangle input data, text, into new commands to be executed. Unlike in GUIs, there is recursion in user interfaces: commands can process themselves. Photoshop, on the other hand, can photoshop its own graphical dialogues, but not actually run those mutations afterwards. As the programmer and system administrator Thomas Scoville puts it in his 1998 paper "The Elements Of Style: UNIX As Literature", "UNIX system utilities are a sort of Lego construction set for word-smiths. Pipes and filters connect one utility to the next, text flows invisibly between. Working with a shell, awk/lex derivatives, or the utility set is literally a word dance."6

In net.art, jodi's "OSS" comes closest to a hypothetic GUI that eats itself through photoshopping its own dialogues. The Unix/Linux/GNU command line environment is just that: A giant word/text processor in which every single function - searching, replacing, counting words, sorting lines - has been outsourced into a small computer program of its own, each represented by a one word command; words that can process words both as data [E-Mail, text documents, web pages, configuration files, software manuals, program source code, for example] and themselves. And more culture-shockingly for people not used to it: with SSH or Telnet, every command line is "network transparent", i.e. can be executed locally as well as remotely. "echo date - ssh user@somewhere.org" builds the command on the local machine, runs it on the remote host somewhere.org, but spits the output back onto the local terminal. Not only do commands and data mutate into each other, but commands and data on local machines intermingle with those on remote ones. The fact that the ARPA- and later Internet had been designed for distributed computing becomes tangible on the microscopic level of the space between single words, in a much more radical way than in such monolithic paradigms as "uploading" or "web applications".

With its hybridization of local and remote code and data, the command line is an electronic poet's, codeworker's and ASCII net.artist's wet dream come true. Among the poetic "constraints" invented by the OULIPO group, the purely syntactical ones can be easily reproduced on the command line. "POE", a computer program designed in the early 1990s by the Austrian experimental poets Franz Josef Czernin and Ferdinand Schmatz to aide poets in linguistic analysis and construction, ended up being an unintended Unix text tool clone for DOS. In 1997, American underground poet ficus strangulensis called upon for the creation of a "text synthesizer" which the Unix command line factually is. "Netwurker" mez breeze consequently names as a major cultural influences of her net-poetical "mezangelle" work "#unix [shelled + otherwise]", next to "#LaTeX [+ LaTeX2e]", "#perl", "#python" and "#the concept of ARGS [still unrealised in terms of potentiality]".7 Conversely, obfuscated C programmers, Perl poets and hackers like jaromil have mutated their program codes into experimental net poetry.

The mutations and recursions on the command line are neither coincidental, nor security leaks, but a feature which system administrators rely on every day. As Richard Stallman, founder of the GNU project and initial developer of the GNU command line programs, puts it, "it is sort of paradoxical that you can successfully define something in terms of itself, that the definition is actually meaningful. [...] The fact that [...] you can define something in terms of itself and have it be well defined, that's a crucial part of computer programming".8

When, as Thomas Scoville observes, instruction vocabulary and syntax like that of Unix becomes "second nature",9 it also becomes conversational language, and syntax turns into semantics not via any artificial intelligence, but in purely pop cultural ways, much like the mutant typewriters in David Cronenberg's film adaption of "Naked Lunch". These, literally: buggy, typewriters are perhaps the most powerful icon of the writerly text. While Free Software is by no means hard-wired to terminals - the Unix userland had been non-free software first -, it is nevertheless this writerly quality, and break-down of user/consumer dichotomies, which makes Free/Open Source Software and the command line intimate bedfellows.

[This text is deliberately reusing and mutating passages from my 2003 essay "Exe.cut[up]able Statements", published in the catalogue of ars electronica 2003.]

References

- [Bar75]

- Roland Barthes. S/Z. Hill and Wang, New York, 1975.

- [Ben97]

- David Bennahum. Interview with Richard Stallman, founder of the free software foundation. MEME, (2.04), 5 1997. http://www.ljudmila.org/nettime/zkp4/21.htm.

- [Kay90]

- Alan Kay. User Interface: A Personal View. In Brenda Laurel, editor, The Art of Human-Computer Interface Design, pages 191-207. Addison Wesley, Reading, Massachusetts, 1990.

- [Sco98]

- Thomas Scoville. The Elements of Style: Unix as Literature, 1998. http://web.meganet.net/yeti/PCarticle.html.

Footnotes:

5Codework by Alan Sondheim, posted to the mailing list "arc.hive" on July 21, 2002

6Thomas Scoville, The Elements of Style: Unix As Literature, [Sco98]

7Yet unpublished as of this writing, forthcoming on the site http://www.cont3xt.net.

Game art: theory, communities, resources

Tom Betts, September 2007

Like all digital media, video-games can be designed, produced, deconstructed and re-appropriated within the context of art. Even though the history of video-games is relatively short, it is already rich with examples of artistic experimentation and innovation. Unlike film or video, games still represent a fairly immature medium, slowly evolving to locate itself in mainstream culture. The majority of games often present simplistic or crude visions of interactivity, narrative and aesthetics, but the medium offers unique potential for the creation of exciting new forms of art. Like any digital medium the evolution of art/games is closely tied to the development of software, hardware and the socio-cultural forms that grow around this technology.

In broad terms there are two general approaches by which artists interface with gaming culture and technology. They can either modify existing games/games systems to produce work ranging from small variations to total conversions. Or they can code their own work from scratch. Of course there are blurred margins between these two practices, in some cases a modification becomes totally independent, or a new code engine may borrow from an existing system.

Modification

Modifying existing game systems is usually easier than programming your own, especially now that game modification is an encouraged part of many product life cycles. Games are frequently produced with modification tools included and developers strive to promote a community of amateur 'add on' designers and 'mapmakers'.

Early game modification grew out of the culture of hacking. In the 8bit era [41] many magazines would publish 'pokes', cheat codes that directly altered the memory locations of a running game to increase the players chances of winning (extra lives etc). It became common to add graffiti-like 'tags' to loading screens or even alter the graphics within the game itself (as is still obvious in the 'warez' community today [42]). Although often requiring arcane machine code knowledge a few intrepid coders re-wrote levels from popular games and made other conversions and modifications to commercial software. While most of these interventions were little more than novelties, some successful conversions highlighted the advantages of an open ended game engine [45] where modification was possible if not encouraged. Soon developers and publishers realised that a stream of modifications could greatly extend the shelf life of a product and in many cases act as free beta testing for subsequent iterations of a series. The most prominent early expression of this was with the Doom/Quake series of games where modifications and tools became widespread.

At this stage it became easy to identify three different types of game modification: Resource Hacking, Code editing and Map/Texture making. Resource hacking is the method closest to original hacking , in this case the user modifies aspects of the program without the use of any publisher-provided tools or code. The second method involves the developers policy to release source code for the game (either for 'add ons' or total conversions. However to make use of such code releases often requires substantial programming skills. ID software (the developers of quake/doom) are one of the few companies that release source code to the public. The final method focuses on using official (and unofficial) tools to manipulate the game content and game play. The third area of practice involves much less technical prowess than the previous two and is increasing in popularity with both mod-makers and developers.

qqq by nullpointer

Due to the increasing range of software tools to aid modification and the support for modding by the industry, a large number of artistic projects have followed this path. Notable works include: JODI's minimalist modification of Wolfenstein (SOD)[1], The psychadelic Acid Arena project [2], Langlands and Bell's Turner prize nominated The House of Osama bin Laden [3], Retroyou's abstraction of the open source X-Plane engine Nostalg [4], nullpointer's network/performance mod of quake3 QQQ [5], the NPR quake [6] modification from quake1 source code, UK artist Alison Mealey's UnrealArt [17], and many more.

Jake by Alison Mealey

Some artists approach the idea of modification in a more social context, disrupting game systems with more interventionist approaches. These modifications are often more time based and performative. The Velvet Strike [7] project introduced the idea of an anti-war graffiti protest into CounterStrike, Joseph Delappe [8] has performed readings of war poetry within multiplayer death match environments, and both RSG [9] and Lars Zumbansen [10] have investigated various 'prepared controller' [43] type setups.

This form of performance (within the game) is closely aligned with the growing machinima movement. In machinima productions game software is used to set, script and record in-game movies. Although prominently used as a cheap but hip film making process (see Red vs Blue [11]), machinima can be a powerful tool to present artistic ideas to a passive audience (see This Spartan Life [12] - Mckenzie Wark)

Games modification can also incorporate hardware hacking. Eddo Sterns Fort Paladin [13] has a PC pressing its own keys in order to control a confused Americas Army recruit, the painstation project and the Tekken Torture [15] events punish the player with physical injury when they lose a game, and Cory Arcangel[16] has produced a series of re-written Super NES [40] cartridges where he has radically altered Super Mario World [44].

Extensive modification can sometimes take the designers/artists so far from the original game engine that the project becomes a Total Conversion (TC). At this point people often consider the work as an independent game-object rather than a direct modification. Artists collective C-Level used heavily modified game engines and content to produce Waco Resurrection [18], a fully playable game, allowing the player to enter a hyper real re-enactment of the Texas Waco siege.

Outside modification / Developing Independently

Although modification provides a relatively easy path in terms of learning curve and software, it can be limiting for certain projects. If artists/programmers require more power or control they can either use existing software engines as a basis for development or they can code their own from scratch. Due to the higher level of skills/resources needed to do this (mainstream games developers often have multi-million budgets and 100+ staff), large projects based on original code are less frequent than modifications. However, rather than pursuing high end technological ambitions, independent developers tend to have more success working with simpler technology.

Working with introductory level systems like java applets or flash movies has allowed artists to produce relatively big impact projects. Flow [19], is an abstract game-environment written by Jenova Chen, SodaPlay [20] is a sandbox physics game by Soda, Samarost [21] is a twisted fairytale adventure, The Endless Forest [22] is a whimsical multiplayer space and N [23] is a minimalist platform game by Metanet. All of these projects have received significant praise despite(and because of) their opposition to mainstream gaming. In some cases these independent projects have broken through to mainstream consoles (flow [19], braid [24], everyday shooter [25])

Spring Alpha by Simon Yuill

Artists with access to larger teams and resources can produce larger projects that move closer to using the same production model as the mainstream. These works can spread over longer timescales and involve complex iterations. The spring_alpha [26] project, directed by Simon Yuill is a project using gaming to explore forms of social organisation. Based on the drawings of artist Chad McCail and the unusual dystopia/utopia we see in the Sims, Spring Alpha has evolved into a number of side-projects and FLOSS developments.

Within mainstream publishing a small minority of titles are often upheld as representing the 'art' side of the industry. Games like Rez, Ico and Okami are frequently cited for their atmospheric environments and abstract aesthetics, Metal Gear Solid 2 is upheld as a postmodern remix and sandbox gaming project, promoted by the Sims, that has led to the current growth and popularity of content/community systems such as Second Life.

Resources

Although still a niche area of practice there are a few notable resources that are well worth investigating in order to learn more about game-art. Selectparks [27] is a collaborative blog and archive for discussing and promoting game art activities. It has a substantial collection of articles and news items and also hosts several artists projects. Based in Australia, the Selectparks team often have some influence on FreePlay [28] a Melbourne based games conference/festival that concentrates on independent and creative development of games culture. Aside from these organisations several influential exhibitions are worth mentioning. Cracking the Maze [29] was probably the first example of a solely game themed art show. Games [30] , an exhibition in Dortmund was a particularly large collection of game based artwork. More recently the Gameworld [31] exhibition at Laboral in Spain attempted to mix mainstream innovation with artistic statements and gamer culture.

Perhaps more than any other forms of digital art, games based art has the benefit, and sometimes barrier, of a strong existing gamer community. This is the place you are most likely to find up to date help, criticism and examples on all aspects of game design and production. Developer/Player blogs and forums often host heated debates and criticism, such discussion is vital for a medium that is slowly adopting more mature forms and content. The Escapist [33] is a weekly e-zine that covers the more thought provoking aspects of gaming culture. Play this Thing [34] is a games review blog that focuses on fringe gaming genres or controversial titles. Gamasutra [46] is a site devoted to both industry articles and critical commentary. Experimentalgameplay.com [32] is a site dedicated to prototyping innovative game ideas in short time frames. From a more production based approach sites like NeHe [36] and GameDev [37] provide links to information on programming in C or 3D, whereas Processing [38] and GotoandPlay() [39] introduce novice programmers to working with java and flash. As with all programming, observing and deconstructing other projects is a great way to train your own skills, luckily most programmers are more than happy to compare notes and offer advice via the forums attached to the above sites.

One crucial piece of advice is to start simple and have achievable goals. Producing or modifying games can be a difficult and time consuming task. It's wise not to be overambitious in your designs and consider the scale of existing art projects that have used similar technology. It is also important to consider how your final work can be distributed or presented as different technologies will require different hardware. Aside from these issues games provide a vast range of expressive forms for creating art and are one of the cheapest ways to access cutting edge technology and distribution.

Notes

[2] http://acidarenaweb.free.fr

[3] http://www.langlandsandbell.demon.co.uk/obl01.html

[4] http://nostalg.org/nostalg_pw.html

[5] http://www.nullpointer.co.uk/qqq

[6] http://www.cs.wisc.edu/graphics/Gallery/NPRQuake

[7] http://www.opensorcery.net/velvet-strike

[10] http://www.hartware-projekte.de/programm/inhalt/games_file_e/work_e.htm#...

[11] http://rvb.roosterteeth.com/home.php

[12] http://www.thisspartanlife.com/episodes.php?id=4

[14] http://www.painstation.de

[15] http://www.c-level.cc/tekken1.html

[16] http://www.beigerecords.com/cory/tags/artwork

[17] http://www.unrealart.co.uk

[19] http://intihuatani.usc.edu/cloud/flowing

[21] http://www.amanita-design.net/samorost-1

[22] http://www.tale-of-tales.com/TheEndlessForest

[23] http://www.harveycartel.org/metanet/downloads.html

[24] http://braid-game.com/news

[25] http://www.everydayshooter.com

[26] http://www.spring-alpha.org

[27] http://www.selectparks.net

[28] http://www.nextwave.org.au

[29] http://switch.sjsu.edu/CrackingtheMaze

[30] http://www.hartware-projekte.de/programm/inhalt/games_e.htm

[31] http://www.laboralcentrodearte.org/portal.do?TR=C&IDR=105

[32] http://www.experimentalgameplay.com

[33] http://www.escapistmagazine.com

[38] http://www.processing.org

[39] http://www.gotoandplay.it

[40] Super Nintendo Entertainment System or Super NES is a 16-bit video game console that was released by Nintendo in North America, Europe, Australasia, and Brazil between 1990 and 1993.

[41] 8 bit era refers to the third generation of video game consoles. Although the previous generation of consoles had also used 8-bit processors, it was in this time that home game systems were first labeled by their "bits". This came into fashion as 16-bit systems were marketed to differentiate between the generations of consoles.

[42] The warez community is a community of groups releasing illegal copies of software, also referred to as 'the Scene'

[43] Prepared controllers are video game input devices such as game pads and joysticks that have been modified, by for instance locking certain buttons or rewiring them.

[44] Super Mario World is a platform game developed and published by Nintendo.

[45] A game engine forms the core of a computer video game. It provides all underlying technologies, including the rendering engine for 2D or 3D graphics, a physics engine or collision detection, sound, scripting, animation, artificial intelligence, networking, streaming, memory management, threading, and a scene graph.

[46] Gamasutra http://www.gamasutra.com

Images

[1] qqq by nullpointer, image courtesy of the artist

[2] Jake by Alison Mealey, image courtesy of the artist

[3] Spring Alpha by Simon Yuill