Collaborative development: theory, method and tools

One of the most significant features of the development of Free Software projects is the immense numbers of people involved. It has been estimated that in the year 2006, almost 2,000 individuals contributed to the coding of the Linux kernel alone, which is just one, admittedly very important, software project amongst the many thousands that are currently in development worldwide [1]. Alongside such numbers, other Free Software projects may be the work of just one or two individuals, or changing sizes of groups who come and go throughout the lifetime of a particular project [2]. One of the reasons for the success of Free Software has been the creation of tools and working practises to support such levels and varieties of involvement. Whilst often tailored for the needs of programming work, many of these tools and practises have spread into other areas and uses, with tools such as the wiki, which provides the technical infrastructure for the online encyclopedia Wikipedia, being one of the best known and most widely used [3].

Collaborative development emphasises the idea of people working together and this is a key aspect of the Free Software ethos. In writing and talking about Free Software, Richard Stallman repeatedly speaks about the 'Free Software community' and the idea of software as something created by a community and belonging to a community, rather than it being exclusively the work of one individual or corporation [4]. 'Collaboration' in itself, however, does not fully cover the full implications of a Free Software practise. Free Software is about making the work you create available for others to also create from. It is a form of production that enables and encourages others to produce. Although it is often associated with the idea of 'appropriative' art and remix culture (in the sense of re-using material that others have created), what Free Software proposes is quite different. This goes beyond the idea of the simple re-use of materials and is better described as a form of 'distributive' practise [5]. Free Software is distributive because in sharing the source code along with the software, it distributes the knowledge of how that software was made along with the product, thereby enabling others to learn and produce for themselves from that. This is something which neither appropriative art or remix culture do. Free Software is something more than just collaboration, or just sharing. It recognises that invention and creation are inherently social acts that produce their own forms of sociability through this process [6]. The collaborative potential of Free Software therefore arises out of this basic principle of distributive production. Given this basis, it is no surprise that many of the actual tools created by the Free Software community for its own use are inherently sociable in their design and are geared towards a process in which people can build and learn together [7].

This chapter provides an overview of some of the development tools currently in use in Free Software projects. Each tool is described in terms of how it works and how it might be applied and integrated into different types of project. In some cases it also discusses the background to the tools, how they came into existence and some of the conceptual underpinnings of how they handle their task. This does not cover all of the tools you would use to create a software project however, only the ones that are necessary for people to work together. For that reason there is no discussion about different code editors, compilers or debugging tools. Nor does it cover issues such as designing and planning a software project from scratch or the typical development cycle involved in that. These are all substantial issues in their own right and are covered elsewhere [8]. The focus here is specifically on tools that help you work with other people, and how to make what you do available to others.

Communication

Any project involving a number of people working together relies on efficient communication between its members. Email and internet chat (or messaging) are the two most widely used forms of online communication and play an important role in any collaborative project. Email is best suited for sending documents and detailed information amongst people, whilst chat is best for realtime discussion. When working in a group it is obviously important to keep everybody in the communication loop, so most projects will make use of a mailing list to coordinate emails between people and a designated chat channel for discussion. As it is also useful to keep a record of communication between people, systems which provide built in storage of messages are a good idea.

Mailman is a mailing list system created as part of the GNU project [9]. It is easy to setup and use, and is provided with a web-based interface that allows people to configure and administer multiple lists through a conventional web-browser. One of its best features is a web-based archive system which stores copies of all messages on the list and makes them available online. The archive allows messages to be searched and ordered in different ways, for example, by date, sender or subject, as well as arranged into topic threads. Each thread starts with a new message subject and follows the responses in a structured order that enables you to see how the discussion around it developed. The archive can be made open to the public, so anyone can read it, or protected so that only people who are subscribed to the list can view it.

It is common for a large project to have multiple mailing lists, each one dedicated to a particular kind of discussion area or group of people. For example there may be one for developers who are writing the code, and another for people writing documentation and instruction materials. There may also be one for users who can ask and discuss problems in using the software, and sometimes additional lists for reporting bugs to the developers and putting in requests for new features in the code. Given all this activity, mailing list archives provide an important information resource about the development of a project, how to use the software created in it, or different approaches to programming problems. They can be a valuable resource, therefore, for someone learning to program, or for someone joining a long-running project who wants to understand its background and personal dynamics better. More recently, a number of academics making studies of FLOSS development have also analysed mailing lists as a way of understanding some of the social structures and interplay involved in such projects [10].

There are many forms of chat and messaging system in use today. IRC (Internet Relay Chat) is one of the oldest systems dating back to the late 1980's and is one of the most widely used. IRC can support both group discussions (known as conferencing) or one-to-one communication, and can also provide a infrastructure for file-sharing [11]. Channels are used as a way of defining distinct chat groups or topics in a way that is analogous with dedicated radio channels. Each channel can support multiple chatrooms which may be created and disposed off on the fly. A chat can be completely open to anyone to join or may require password access. For extra security IRC chats can also be encrypted. IRC is not itself a tool, but rather a protocol that enables online discussions. To use IRC requires a server for hosting the chats and clients for each of the participants. There are many public IRC servers, such as freenode.net, which provide free IRC channels for people, and these are often sufficient for most small-scale projects. Larger projects may wish to have their own dedicated IRC servers.

When working together it is common for programmers to have an IRC client running on their machine where they can ask quick questions to other developers or handle discussions in a more immediate and flexible manner than email permits. IRC can also be an excellent way of taking someone through a process step-by-step remotely. Whilst having a public archive of a mailing list is common, it is less usual to store IRC discussions. As IRC is a sociable medium there can be a lot of ephemeral or trivial content exchanged between people (as in everyday chat between friends) and storing all of this for public consumption is probably not worth the disc space. All good IRC clients, however, have built-in logging capabilities which allow the user to store the discussion in a text file for later reference.

Logo of BitchX, a free IRC client

There are a number of IRC clients for GNU/Linux. ircII is the oldest IRC client still in use, and one of the first to be created. BitchX is a highly popular offshoot of ircII originally written by "Trench" and "HappyCrappy" and has a certain style of its own synonymous with aspects of hacker and l33t culture. irssi is a more recent client written from the ground up to be highly modular and extensible. All of these clients can be scripted to handle various forms of automated tasks, such as chat bots, or integrate with other processes [12].

Sharing Code

When Richard Stallman first made EMACS available to the world, and Linus Torvalds released Linux, people generally made feedback and contributions to the code via newsgroups and email communication [13]. This is fine for small-scale projects, but as the number of people and amount of work involved in a project grows, this kind of interaction between the code and developers becomes quickly unmanageable. In the late 1980's, Dick Grune, a programmer working on the Amsterdam Compiler Kit (ACK) project, wrote a set of scripts for making changes to source code files in a way that ensured the code could be changed at different times by different people without accidentally losing one person's input [14]. These scripts were called the Concurrent Versions System (CVS), as they enabled different versions of the code to exist side by side as well as be integrated into one another. They were later developed into a self-contained tool that is still one of the most widely used 'version control' or Source Code Management (SCM) systems.

Alongside CVS, a number of other SCMs have become popular, these include Subversion (SVN), Git and darcs (David's Advanced Revision Control System) [15]. Each has its own particular features and the design of a particular SCM system often carries an implicit model of code development practises within it. There are, however, various common features and tasks that are standard across different SCMs. SCMs generally work on the basis that the source code for a given software project is organised into a set of distinct files. The files are stored in a 'repository' which is often simply a normal file directory on a computer containing both the source files and meta-data (background information) about the changes that have been made to them - sometimes the meta-data is held separately in a database. Programmers can work on the source files independently, submitting their changes and additions to the repository and obtaining copies of the files as they are changed by other programmers. The SCM manages this process and enables the different contributions to be combined into a coherent whole.

The main tasks normally performed by a SCM are:

- to store each new version of a source file without erasing previous versions, and to enable earlier versions to be retrieved. These tasks are often known as 'committing' changes and 'checking out' revisions.

- to associate specific changes in a source file with a specific programmer. This is usually done by requiring programmers to log into the SCM under a specific username each time they 'commit' their changes to the code.

- to provide a history of changes in a given source file and enable files to be compared to one another. A comparison is often called a 'diff' after the UNIX commandline tool for displaying differences between two files.

- to warn or indicate when two or more programmers have attempted to change the same lines of code, known as a 'conflict'.

- to enable parallel versions of the source files to be maintained alongside each other. This is known as 'branching', with each parallel version being a separate branch.

- to combine different parallel versions of a source file into one final version, known as 'merging'.

One of the most significant differences between different types of SCM lies in the kind of repository system that they use. The key distinction being between those that use a centralised repository and those that are decentralised. CVS and SVN both use centralised repositories. In this case there is only one copy of the repository which exists on a specific server. All the programmers working on the project must commit their changes and checkout revisions from the same repository. Git and darcs both use decentralised repositories. With this approach, every programmer has a complete copy of the repository on their own machine, and when updating code commits their changes to that local version. The different repositories are then periodically updated to bring them into sync with one another through use of a networking mechanism. This communicates between the different repositories and merges their changes into one - a process known as 'pulling' and 'pushing' the changes between repositories. The decentralised approach is, in some ways, similar to a situation on a centralised server in which each programmer is working in their own branch. This may seem like a counter-intuitive approach towards maintaining coherence between the different programmers' work, and, perhaps for this reason, centralised systems such as CVS and SVN are often the more popular. Decentralised SCM systems have, however, shown themselves to be extremely effective when dealing with very large projects with many contributors. The Linux kernel, with nearly 2,000 programmers and several million lines of code, is one such large project, and the Git system was specifically written by Linus Torvalds for managing its development. The reason for the effectiveness of decentralised repositories for large projects may be that with the greater the number of people making changes to the code, the greater the amount of 'noise' this activity produces within the system. Within a centralised system this noise would affect everybody and, in doing so, amplify itself in a kind of feedback loop. Within a decentralised system, however, the activity, and resultant 'noise', is spread over many smaller areas thereby making it more contained and less likely to effect others. With a large project furthermore, in which many small groups may be focusing on different areas of its development, having multiple repositories also enables each group to focus on the key issues that it is addressing. In this sense each repository articulates a different 'perception' of the project.

Darcs has a very particular approach to updating code, called the "Theory of Patches", which derives from author David Roundy's background as a physicist [16]. This adopts concepts from Quantum mechanics and applies them to a model of code management in which any kind of change to the source code is abstracted as a 'patch' [17]. A variety of different operations are implemented to apply a patch to a repository. The advantage of Roundy's patch system is that it enables a variety of tightly tuned forms of merging to be performed that other SCM systems do not support, such as only updating replacements of a specific word token within different versions of source files (most SCM systems would change each entire line of code in which the token is found), or applying changes in a given order or combination (called sequential and composite patches).

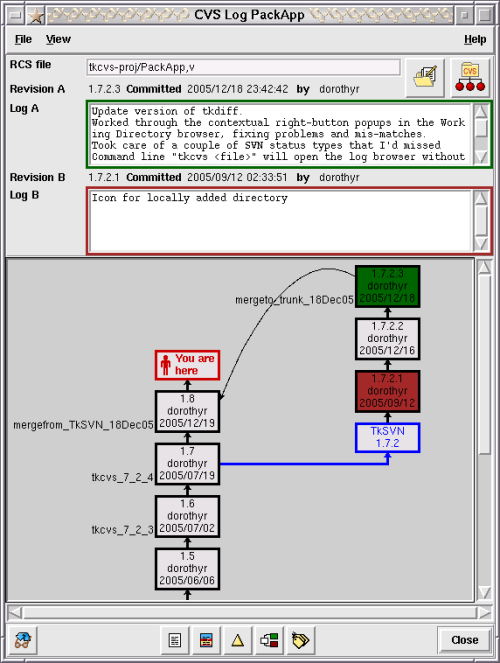

For the programmer, interacting with a SCM system is generally done through a simple commandline tool. This enables the programmer to more easily integrate the SCM interface with whatever code editor they prefer to work with, and many code editors, such as EMACS, provide a mechanism through which the SCM can be directly accessed from the editor [18]. Various graphical SCM clients have also been developed however. The TkCVS and TkSVN tools provide GUI based interaction with the CVS and Subversion repository systems [19]. In addition they can display visual charts showing the structure of the source files within the repository, and mappings of branches, revisions and merges within a project.

Screenshot of Branch Browser in TkCVS

As with mailing lists, code repositories also provide a great deal of information on how a software project evolves. A number of tools have been developed to generate statistics and visualisations of different aspects of a repository, such as showing which files the most activity is focused around and the varying degrees in which different programmers contribute to a project [20].

A number of free public code repositories are available on the internet, such as the GNU Project's Savannah repository. Alongside the SCM system, these often provide a packaged set of tools for managing a project. These are discussed in more detail below.

Sharing Ideas

A good piece of software is more than just so many pages of code. A good piece of software is a good set of ideas expressed in code. Sometimes those ideas are expressed clearly enough in the code itself, and there are those who argue that a good programmer is one who can express herself or himself clearly in this way [21]. Sometimes, and perhaps more often with larger projects, the ideas are not so easily contained in a single page of code or are implicit more within its bigger structure or how particular components within a program interact with one another.

One approach to this issue has been to provide comments and documentation notes directly within the text of the program code itself, and most programming languages include a special syntax for doing this. Some languages, such as Forth and Python, have taken this idea a step further and enable the documentation notes to be accessible from within the code whilst the program using it is running [22]. For almost all programming languages, however, a set of tools known as 'documentation generators' are available which can analyse a set of source files and create a formatted output displaying both the structure of the code and its accompanying comments and notes. This output can be in the form of a set of web pages which directly enable the documentation to be published online, or in print formats such as LaTeX and PDF. 'Document generators' are often dedicated to a particular programming language or set of languages. PyDoc, EpyDoc and HappyDoc are all systems designed specifically for Python [23]. Doxygen is one of the most widely used document generators and supports a number of languages including C++, Java, and Python [24]. When used in conjunction with Graphviz (a graph visualisation tool), Doxygen can also create visual diagrams of code structures that are particularly useful for understanding the object-orientated languages that it works with [25].

Another, quite different, approach lies in the use of Design Patterns. Design Patterns are a concept adapted from the work of architect Christopher Alexander. Alexander was interested in developing a means through which architects and non-architects could communicate ideas of structure and form, so that non-architects, in particular, could envisage and describe various forms of domestic and urban building systems and thereby have greater control over the design of their built environment [26]. As applied to programming, Design Patterns provide a means of articulating common programming paradigms and structures in ways that are separate from actual code and can be explained in ordinary language [27]. They focus on the structure and concepts, the ideas, behind the code, rather than the specifics of how a particular piece of code is written. This allows ideas to be transferred more easily from one project to another even if they do not share the same programming language. In 1995, the Portland Pattern Repository was set up to collect and develop programming Design Patterns through a SCM-like system. This system was the first ever wiki [28]. A wiki is basically a web-based text editing system that provides a simplified form of version control like that used in CVS. The wiki created a simple yet robust way of enabling the content of web-pages to be updated in a collaborative fashion. It was quickly realised that this could be applied to all manner of different topics that could benefit from collaborative input, and the wiki spread to become one of the most widely used content management systems on the internet, with the most famous example being the Wikipedia encyclopedia [29].

Nowadays, a whole range of different wikis are available, ranging from simple text-only systems to more sophisticated ones supporting images and other media content [30]. Within a programming project wikis provide a simple and effective publishing system for updating information and documentation related to the project. They can augment the primarily technical information produced through a documentation generator to provide more descriptive or discursive information such as user manuals and tutorials.

Project Management

The various tools described so far can all be combined into more comprehensive packages that provide a complete framework for managing a software development project. Often these are available for free through public development repositories such as Savannah and BerliOS, although it is also possible to set up your own system independently. Both Savannah and BerliOS are specifically geared towards supporting fully Free and Open Source projects. Savannah is run by the GNU Project and BerliOS is run by the German group FOKUS, both are not-for-profit organisations [31]. SourceForge provides a similar free service but is run as a commercial enterprise [32]. These sites are often described as 'developer platforms', a platform in this case meaning a web-based service that facilitates or provides an infrastructure for other people's projects [33].

To use one of these platforms you must first register as a member and then submit a description of your proposed project, each site will provide details of what kind of information they wish you to provide in this description. The project will be reviewed by a selection panel within the organisation or user community that runs the platform and, if accepted, you will be given an account under which your project will be hosted. In addition to resources such as a code repository and mailing lists, all of these platforms also provide tools such as bug tracking systems and web-site facilities for publishing development news and documentation.

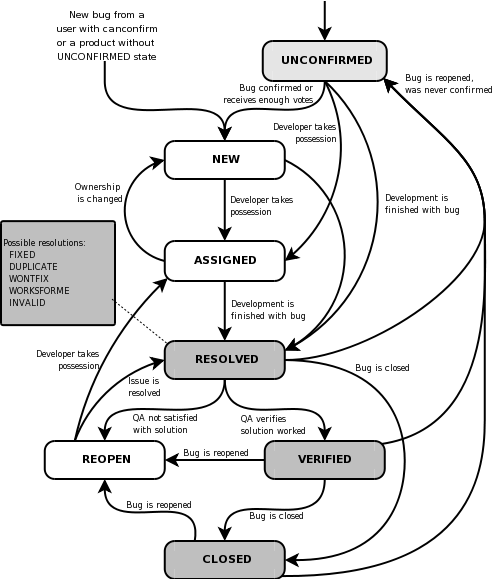

Bug tracking systems are tools that enable users and developers working on a project to report bugs they have discovered in the software. These reports can then be parcelled out amongst the developers, who will report back to the tracking system when the bug has been fixed. The status of each bug report is normally published through an online interface. This is particularly useful for any medium-to-large scale project and provides one useful development mechanism that non-programmers can contribute to. One well-known and widely used bug tracking tool is Bugzilla which was originally created for the development of the Mozilla web-browser [34].

Bugzilla Lifecycle diagram

A similar service is a 'feature request' system. This enables users and developers of a software project to submit requests and ideas for features that are not currently part of the project but could be implemented at a later stage. As with the bug tracker it provides a good way for non-programmers to contribute to a project. The Python project is one example of a project that has made good use of this facility and has its own system called PEP, short for Python Enhancement Proposal [35].

If you wish to set up your own development platform a number of packages are available. Savane is the system used by Savannah and BerliOS [36]. Trac is another system more widely used in smaller projects. It includes a wiki system and is much easier to customise in order to create a self-contained project site with its own look [37].

Sharing spaces

Whilst online development has been a feature of Free Software, it would be wrong to assume that everything happens exclusively online. The online world supports a rich variety of social groupings many of which have equivalents within the offline world. These often provide strong social contexts that link Free Software practise to local situations, events and issues. Linux Users Groups (LUGs) are one of the most widespread social groups related to Free Software. These groups normally include a mix of people from IT professionals and dedicated hackers, to hobbyists and other people who use GNU/Linux and other forms of Free Software in their daily lives. LUGs are usually formed on a citywide basis or across local geographic areas, and there will most likely be a LUG for the town or area in which you live [38]. They combine a mailing list with regular meetings at which people can share skills, discuss problems and often also give talks and demonstration of projects they are working on or are interested in. Similar groups with a more of an artistic angle to them include Dorkbots, which include all forms of experimental tinkering and exploration of technology, and groups such as Openlab which operate more like an artists collective for people working with Free Software-based performance and installation [39].

Nerdcore Central, hackmeet

Hacklabs and free media labs are actual spaces, setup and run on a, mostly, voluntary basis. A typical lab will make use of recycled computer hardware running Free Software and providing free public access to its resources. As spaces they can provide a base for developing projects, whether that involves actual coding or a place for the developers to meet. Many labs also provide support for other local groups, such as computers for not-for-profit organisations. Hacklabs generally have a strong political basis to them and will often be linked with local Indymedia and grassroot political groups [40]. They are frequently, though not necessarily, run from squatted buildings. Such action makes a conscious link between the distributive principles of Free Software and the distributive principles of housing allocation promoted by the squatting movement [41]. Hacklabs have developed primarily in Italy and Spain, such as LOA in Milan and Hackitectura in Barcelona, but the Netherlands and Germany also have many active hacklabs, such as ASCII in Amsterdam and C-Base in Berlin [42]. Historically, these have had close associations with the Autonomist and left-wing anarchist groups. Free media labs are usually less overtly political, often with an emphasis on broader community access. Historically they can be seen to have grown from the ethos of the community media centres of the 1970s and 80s, with Access Space, set up in Sheffield in 2000, being the longest-running free media lab in the UK [43]. Free media labs are more likely to use rented or loaned spaces and may even employ a small number of staff. It would be wrong, however, to suggest that there are sharp divisions between hacklabs and free media labs, rather, they present different models of practise that are reflective of the social and economic contexts in which they have emerged. The government-sponsored Telecentros in Brazil offer a different example of such spaces, varying from providing low-cost public computer access to supporting more radical projects such as MetaReciclagem who focus on training people to become self-sufficient with technology [44]. An important offshoot of MetaReciclagem were the Autolabs setup by the Midiatactica group in the favelas of Sau Paulo [45].

A different use of space to bring people together is found in the many forms of meetings and collective events that are characteristic of the Free Software world. Again these range from self-organised events such as hackmeets to more official festivals and conferences. These may either act as general meeting points for people to come together and exchange contacts, skills and ideas, or as more focused short-term projects that aim to achieve particular tasks such as pulling resources to complete a software project. Examples at the more commercial end of the spectrum include the Debian conference, DebConf, and Google's Summer of Code [46]. The Chaos Computer Club meetings and TransHack are examples from the more grassroots end of things, whilst Piksel and MAKEART are two examples of artist-led events that combine aspects of a hackmeet with an arts festival [47].

Starting your own project

If you are starting up a Free Software project of your own for the first time, the best thing to do is take a look around at how other projects are run and the tools that they use. Take a bit of time to familiarise yourself with the different tools available and pick the ones that feel best suited to your needs and way of working. A good way to do this is to create a little dummy project on your own machine and test out the tools and processes with it. Another way of building up experience is to join an existing project for a short while and contribute to that, or even just join the developers mailing list to see what kind of issues and ideas come up there. One of the best ways you will find support is through the Free Software community, so make contact with your nearest LUG, see if there are any hacklabs and free media labs in your area and take a trip to the next hackmeet, conference or festival that comes your way.

If you are working with other people, see what the more experienced ones within the group can tell you about how they work and what tools they use. If your entire development team is new then it is probably best to come to a collective decision about what tools you are working with and choose the same set of tools for everyone so that you are learning the same things together. There are certain tools which you will have to share anyway, for example, you will all have to use the same SCM whether it is CVS, SVN, darcs or something else. Other tools can be different among different developers without causing conflicts. You should be able to use different code editors and different IRC clients for example without any problems.

Assuming that your first project will probably not be too ambitious, you may not need to use tools such as bug trackers, however, there is no harm in integrating these into your working process in order to build up a sense of how they operate. If you want to utilise the full range of development tools it is probably best to opt for an account with a public developer platform such as Savannah or BerliOS, or to use an all-in-one package such as Trac.

Not just code - Free Software as artistic method

The early years of internet art were characterised by a number of projects based around large-scale public collaborations often in the form of texts or images that could be added to and altered by different people [48]. These projects emerged at a time when Free Software was only just beginning to gather momentum and so they did not make use of the approaches it offers. There is no reason why a collaborative project that is producing something other than computer code could not make use of the tools and practises described here, however, and it has been suggested that a CVS system can be understood as a form of 'collaborative text' in its own right [49].

None of these early projects, however, fully realises the idea of a Free Software practise as an artistic method. For all the collaborative nature of their construction, these projects often focus on a self-contained artefact as their sole end. They are collaborative but not distributive. More recently, however, a number of projects and approaches have been developed which not only use Free Software tools to create the work, but also realise a form of the Free Software ethos in how the projects are engaged with. The Openlab group in London have been developing small software systems for supporting improvised group performances which are themselves open to be reprogrammed during performance [50]. Social Versioning System (SVS) is a project which combines reprogrammable gaming and simulation systems with an integrated code repository. As with the Openlab tools, reprogramming is one of the key modes of engagement, but in linking this to a repository in which the changes and contributions of players can be examined, it aims to present coding itself as a form of dialogue, with the gaming projects critically exploring forms of social systematisation and urban development [51]. Plenum and Life-Coding are two performance projects which have adopted a similar approach [52]. All of these projects have, in different ways, adapted aspects of Free Software development tools and practises. Whilst less consciously designed as an artwork in itself, the pure:dyne project also demonstrates such an approach. Here, artists have collaborated in the development of a version of the GNU/Linux operating system specifically geared towards using and supporting Free Software based artistic tools and projects [53]. Pure:dyne is built on top of dyne:bolic, a version of GNU/Linux for artists and activists focusing on streaming and media tools [54]. Dyne:bolic was made partly possible through the Linux From Scratch project, which publishes guides for people wishing to create their own version of the GNU/Linux operating system [55]. This chain of development through successive projects is an excellent example of the distributive principle in action.

It would be wrong, however, to see these projects as a development from the earlier experiments with networked collaborative artworks. A much stronger analogy lies with the collective improvisation groups of the 1960s such as the Black Arts Group of St Louis (BAG) or the London-based Scratch Orchestra. In a move which in many ways pre-empts the hacklabs of today, the Free Jazz group BAG converted an abandoned warehouse into an inner-city 'training centre' jointly run by the group and local community. The space supported rehearsals and performances by BAG combined with various forms of public classes, workshops and discussions groups focused around issues affecting the local community. Here the collaborative musical practise of the jazz ensemble is structured upon, and reflective of, the wider distributive principle of the arts space in which they operate [56]. Another analogy is evident in the Scratch Orchestra who, like BAG, were an improvised music collective. Participation was open to anyone who wished to join regardless of musical background or experience. One of the key aspects of its practise were the development of 'scratch books' in which Orchestra members collated their own performance scores using whatever forms of notation they wished - from actual musical notation to abstract diagrams, written instructions and collaged found materials [57]. The scratch books were exchanged between different members who could use, alter and adapt from each other's work. Some versions of the scratch books were published under early forms of copyleft licences in which people were not only free to copy, but also encouraged to submit changes and additions that would be incorporated into later versions [58]. This was the embodiment of an idea that Cornelius Cardew, one of the founding members of the Scratch Orchestra, summarised in the statement: "the problems of notation will be solved by the masses." [59] Programs are notations just as music scores are, and we can clearly see how Cardew's sentiment applies as much to the practise of Free Software as it did to the music of the Scratch Orchestra.

Like the Free Software projects of today, these groups sought to distribute the knowledge and skills of production as an integral part of what they produced, but they also sought to explore and expose the social relations through which people worked. They deliberately challenged the notion of artistic authorship as the exclusive act of a single, socially disengaged, individual - one which still dominates the artworld today - as well as being critically aware of issues of power and hierarchy within collective practise. It is not just the distribution of knowledge, but also the distribution of access and power that these groups engaged with and faced up to. After several years of productive activity, the Scratch Orchestra fell apart due to internal tensions. Cardew put this down to a lack of sufficient self-criticism amongst its members, while others attributed it to one group seeking to exert its influence unfairly over the Orchestra as a whole [60]. Ultimately these are issues which any form of collaborative development needs to address and be critically aware of in some form, for, as the Scratch Orchestra discovered, working with others is not always an easy or inherently egalitarian process [61]. The success of any such project rests, not only in its ability to create something through collaboration, but in developing an awareness of what is at stake in collaboration itself.

Notes

1. see Jonathan Corbet, 2007, "Who wrote 2.6.20?", http://lwn.net/Articles/222773/ and David A. Wheeler, c.2006,"Counting Source Lines of Code", http://www.dwheeler.com/sloc/

2. there have been a number of studies on the structure of FLOSS development teams, see, for example: Rishab Aiyer Ghosh, 2003, "Clustering and dependencies in free/open source software development: Methodology and tools", http://www.firstmonday.org/issues/issue8_4/ghosh/index.html

3. Wikipedia is an online encyclopedia that anyone can contribute to: http://www.wikipedia.org

4. Richard Stallman, "The GNU Project", http://www.gnu.org/gnu/thegnuproject.html, also in the book Richard Stallman, 2002, Free Software, Free Society: Selected Essays of Richard M. Stallman, GNU Press; Boston.

5. for a more detailed account see Simon Yuill, 2007, "Free Software as Distributive Practise", forthcoming

6. this should not be confused with the idea of 'social media' which has become prominent in an approach to online commerce known as Web 2.0, Free Software foregrounds the social basis of production, whereas, Web 2.0 seeks to commodify social relations, see Dmytri Kleiner and Brian Wyrick, 2007, "InfoEnclosure 2.0", in MUTE, vol 2 issue 4, also online: http://www.metamute.org/en/InfoEnclosure-2.0

7. people can also build and learn apart, a common example being when one software project makes use of a library or codebase developed by a different group of people without any direct communication or collaboration between the people involved.

8. there are numerous online guides for programming with Free Software tools, such as Mark Burgess and Ron Hale Evans, 2002, "The GNU C Tutorial", http://www.crasseux.com/books/ctutorial/, Mark Burgess, 2001, "The Unix Programming Environment", http://www.iu.hio.no/~mark/unix/unix_toc.html, Richard Stallman, 2007, "GNU Emacs manual", http://www.gnu.org/software/emacs/manual/emacs.html, and Eric Raymond, 2003, "The Art of Unix Programming", http://www.catb.org/~esr/writings/taoup/html/

9. http://www.gnu.org/software/mailman. For a discussion of the ideas behind mailman see: Barry Warsaw, 2000, "Mailman, the GNU Mailing List Manager", http://www.linuxjournal.com/article/3844

10. a good example is Nicolas Ducheneaut's OSS Browser, http://www2.parc.com/csl/members/nicolas/browser.html

11. for general information on IRC see http://www.irc.org and http://www.irchelp.org and Jarkko Oikarinen, undated, "IRC History", http://www.irc.org/history_docs/jarkko.html

12. ircII: http://www.eterna.com.au/ircii, irssi: http://irssi.org, BitchX: http://www.bitchx.org

13. this is described in Richard Stallman, "The GNU Project", ibid., and Eben Moglen, 1991, "Anarchism Triumphant: Free Software and the Death of Copyright", http://emoglen.law.columbia.edu/publications/anarchism.html

14. Dick Grune, Concurrent Versions System CVS. http://www.cs.vu.nl/~dick/CVS.html ACK was Stallman's original choice for a compiler in the GNU Project, when he approached Grune about using ACK however, Grune refused and, as a result, Stallman had to create his own compiler, which became GCC. ACK has since become obsolete whereas GCC is one of the most powerful and popular compilers currently in use today.

15. CVS: http://www.cvshome.org, SVN: http://subversion.tigris.org, Git: http://git.or.cz, darcs: http://darcs.net. For a detailed discussion of how Git works see: Jonathan Corbet, 2005, "The guts of git", http://lwn.net/Articles/131657/

16. David Roundy, undated, "Theory of patches", http://darcs.net/manual/node8.html#Patch

17. 'patches' are a common name for small changes to a code file, the repository is called a tree in Roundy's theory - all repositories have a tree-like structure.

18. the EMACS code editor was originally written by Richard Stallman, http://www.gnu.org/software/emacs

19. TkCVS and TkSVN: http://www.twobarleycorns.net/tkcvs.html

20. one example is Gitstat, which produces online visualisations of activity within Git repositories: http://tree.celinuxforum.org/gitstat. Stats for the Linux kernel are available at: http://kernel.org

21. This idea is best represented in Donald Knuth's notion of 'literate programming', see: Donald E. Knuth, Literate Programming, Stanford, California: Center for the Study of Language and Information, 1992, CSLI Lecture Notes, no. 27.

22. Forth: http://thinking-forth.sourceforge.net, Python: http://www.python.org

23. PyDoc: http://docs.python.org/lib/module-pydoc.html, EpyDoc: http://epydoc.sourceforge.net, HappyDoc: http://happydoc.sourceforge.net

24. http://www.stack.nl/~dimitri/doxygen

26. Christopher Alexander, et al., A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction, New York: Oxford University Press, 1977, for a discussion of Alexander's ideas applied to software development see: Richard Gabriel, 1996, "Patterns of Software: tales from the Software Community", Oxford University Press; New York, PDF available online: http://www.dreamsongs.com/NewFiles/PatternsOfSoftware.pdf

27. the classic text on software design patterns is: Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson, and John Vlissides, 1995, Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software, Addison-Wesley. Design patterns are not specific to Free Software practise, and did not originate out of it, but have become popular amongst many programmers working in this way.

29. see note 3 above.

30. For a comparison of different wiki systems see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparison_of_wiki_software

31. Savannah: http://savannah.gnu.org, BerliOS: http://www.berlios.de

33. for a discussion of web platforms in relation to artistic practise, see: Olga Guriunova, 2007, "Swarm Forms: On Platforms and Creativity", in MUTE, vol 2 issue 4, also available online: http://www.metamute.org/en/Swarm-Forms-On-Platforms-and-Creativity

35. http://www.python.org/dev/peps

36. https://gna.org/projects/savane

38. there is a listing of LUGs organised by country available at: http://www.linux.org/groups, see also: http://www.gnu.org/gnu/gnu-user-groups.html

39. Dorkbots are worldwide, the main site from which all Dorkbot groups can be accessed is: http://www.dorkbot.org. Openlab groups currently exist in London, Glasgow, Amsterdam and Brussels, the two most active are in London: http://www.pawfal.org/openlab, and Glasgow: http://www.openlabglasgow.org

40. Indymedia is a worldwide movement to create independently produced news coverage. There are many local Indymedia groups across the world, the main site is at: http://www.indymedia.org

41. for background and discussion about the squatting movement see Anders Corr, 2000, No Trespassing!: Squatting, Rent Strikes and Land Struggles Worldwide, South End Press, and Advisory Service for Squatters, 2005, The Squatters Handbook, Freedom Press: London

42. Hackitectura: http://hackitectura.net, LOA: http://www1.autistici.org/loa/web/main.html, ASCII: http://www.scii.nl, C-Base: http://c-base.org. For a listing of different hacklabs internationally see: http://www.hacklabs.org. For a good overview of typical hacklab activities see: hydrarchist, 2002, Hacklabs - A Space of Construction and Deconstruction, http://info.interactivist.net/article.pl?sid=02/07/23/1218226&mode=neste...

43. http://www.access-space.org Access Space grew out of the Lowtech project which started earlier in the mid-1990s.

44. http://www.metareciclagem.org

45. http://autolabs.midiatatica.org, see also: Ricardo Rosas, 2002, "The Revenge of Lowtech: Autolabs, Telecentros and Tactical Media in Sao Paulo", in Sarai Reader 04: Crisis / Media, Sarai Media Lab; Bangalore, also available online: http://www.sarai.net/publications/readers/04-crisis-media/55ricardo.pdf

46. DebConf: http://www.debconf.org, Summer of Code: http://code.google.com/soc

47. Chaos Computer Club: http://www.ccc.de, TransHack: http://trans.hackmeeting.org, Piksel: http://www.piksel.no, MAKEART: http://makeart.goto10.org

48. two of the earliest such projects include Roy Ascott, 1983, The Pleating of the Text: A Planetary Fairy Tail, (see Frank Popper, 1993, Art of the Electronic Age, Thames and Hudson: London, p. 124) and SITO: http://www.sito.org, an online collaborative image bank started in 1993, for an overview of SITO's history see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SITO

49. Florian Cramer, 2000, "Free Software as Collaborative Text", http://plaintext.cc:70/essays/free_software_as_text/free_software_as_tex...

50. http://www.pawfal.org/openlab/index.php?page=LaptopDrummingCircle

51. http://www.spring-alpha.org, and http://www.spring-alpha.org/svs

52. Plenum was part of Node.London, 2005, Life-Coding was presented at Piksel in 2007.

53. http://puredyne.goto10.org

55. http://www.linuxfromscratch.org

56. Benjamin Looker, 2004, Point From Which Creation Begins: The Black Artists' Group of St. Louis, St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press. For BAG this was an approach that was shared with the wider Black Arts Movement: "Seeing their art as a communal creation, national leaders of the Black Arts Movement had rejected Romantic and post-Romantic notions of the individual artist working in isolation or estrangement from his social context. Instead, they stressed art's functional roles, urging that it be created in a communitarian and socially engaged stance.", Looker, p. 66

57. for an overview of the Scratch Orchestra see Cornelius Cardew, 1974, Stockhausen Serves Imperialism and Other Articles, Latimer New Dimensions: London, PDF available online: http://www.ubu.com/historical/cardew/cardew_stockhausen.pdf. Extracts from the scratch books were collated and published in Cornelius Cardew (editor), 1974, Scratch Music, MIT Press: Massachusetts, MA.

58. see for example Cornelius Cardew (editor), 1969, Nature Study Notes, Scratch Orchestra: London: "No rights are reserved in this book of rites. They may be reproduced and performed freely. Anyone wishing to send contributions for a second set should address them to the editor: C.Cardew, 112 Elm Grove Road, London SW13.", p. 2

59. Cardew, 1974, p. 88.

60. different perspectives on this are provided in Cardew, ibid, Stefan Szczelkun, 2002, The Scratch Orchestra, in "Exploding Cinema 1992 - 1999, culture and democracy", available online: http://www.stefan-szczelkun.org.uk/phd102.htm, and in Luke Fowler's film documentary about the Scratch Orchestra, "Pilgrimage From Scattered Points" (2006).

61. For a more critical perspective on colloborative working see Ned Rossiter, 2006, Organized Networks: Media Theory, Creative Labour, New Institutions, NAi Publshers: Rotterdam, and Martin Hardie, The Factory Without Walls, http://openflows.org/%7Eauskadi/factorywoutwalls.pdf

Images

[1] Logo of BitchX, a free IRC client.

[2] Screenshot of Branch Browser in TkCVS.

[3] Bugzilla Lifecycle diagram. Included in the source package for Bugzilla and available under the Mozilla.org tri-licence (MPL, GPL, LGPL). For use in the Bugzilla article.

[4] Nerdcore Central, hackmeet, photo by Armin Medosch, from: www.thenextlayer.org/node/74